Sandrine Schaefer

In addition to co-curating Rough Trade II, Sandrine created Second Skin 2012. The following is an interview between Sandrine and Philip Fryer of The Present Tense.

Philip Fryer: Can you expand of some of the objects and actions used in your piece?

SS: I work site-sensitively and have been creating most of my recent work outside of designated art contexts. Travel is essential to my practice. Second Skin was an exercise in merging multiple contexts through body memory. Every time the body inhabits a space, it collects traces. The objects, materials, and actions were some of my conscious collections from places I have traveled in the past year.

Small fans were ubiquitous in buses in the cities I traveled in Mexico, as well as dried arbol chillis. I wanted to ignite my audience’s sense of smell, so I tied the arbol chilis to small flesh colored fans to spread the faint aroma that I remember from the food markets in Oaxaca City. This piece was intended to be viewed from the street and/or inside one of the storefront windows. I wanted to break the barrier of the “Performance space” and let the viewers know that they could enter, despite the way the space looked. I summoned the audience into one of the windows and invited the audience one by one to hold eye contact with me through the fan. As we connected with this intimate action, they were able to smell the chilis and given the sensation of feeling air on their face.

The other action I engaged in occurred in the 2nd window. I had arbol chilis in my shirt that fell to the ground as I peeled my shirt up. I repeated the action of peeling my shirt off of my body, reaching above my head and exposing my back. The back has become an important to my recent work. It is one of the strongest and vulnerable parts of the body. It is also a gender neutral. With each reach, I balanced on my tip-toes. As my heels lifted, soft sound could be heard. I recently went on a family vacation to an amusement park. While I was there, I recorded t-shirts that I saw people wearing. I was intrigued by

1. What people chose to put on their bodies (their second skin)

and

2. The absurdity of these phrases taken out of context.

The sound piece is a recording of me reading the t shirt phrases as montone as possible, trying to neutralize each word.

PF: How is the body a place?

SS: It contains the soul, the memory, it is home to billions of organisms, the kind of creatures that live on your eyelashes. It is an ecosystem.

PF: What memory/impression did Chicago leave on your body?

SS: I have done this action of reaching up on my toes countless times, both in pieces and in my daily life. It was particularly difficult in Chicago. Trying to maintain eye contact through the fan before this action threw off my balance. I had to learn how to negotiate how unstable my body felt in a way that I wasn’t expecting or used to.

PF: Would you say that your work has the “Boston flavor”? If so, how?

SS: Like I said earlier…places leave traces. I’ve been working in Boston for almost 15 years. It definitely has influenced my process and esthetic.

PF: One of your actions was interrupted, how did you deal with that? Is this a common occurrence during your work?

SS: This is where the word “performance art” can cause some trouble. If people think they are watching a “performance,” as defined by traditional performing arts disciplines, there can be the expectation that the audience’s role is to sit stagnant, waiting to be entertained. My work is just as much about my audience’s experience as my own, so I want them to experience my work in ways that feel authentic. When an audience member unplugged my fan during my performance, it was an indication that I was successful in this intent. This doesn’t happen to me very often, but when it has, I don’t judge it. It’s just another form of witnessing. I used it as an indicator to move on to the next action of my piece.

PF: How has being an artist influenced your curatorial work and being a curator influenced your artwork?

SS: Both my artistic and curatorial practice work in symbiosis. I believe that artists have the responsibility to champion the work that inspires them. I find it helpful to my own practice to experience the work that other artists are making and hear what artists in other places are inspired by. It keeps me motivated and my work current. Joseph sums up the Artist/Curator relationship really well!

PF: How has teaching impacted your practice?

SS: Teaching is like any collaboration in that it has forced me to identify, distill, and communicate processes and strategies to others. It has made me more patient, and it’s helped me look at experiential art differently. One of the most challenging parts of being an artist is the balancing act between creating a consistency in your work while still being able to work outside of your comfort zone to ensure growth. Having the opportunity to watch someone else work through their process has inspired me to push myself in my own practice.

PF: Shorter, timed performances were absent in your work for a while, can you talk about returning to this format?

SS: I would disagree with that. Through my project, Being (small), I have done many shorter, pieces. My rule for that project is to stay in a space for as long as my body or the space will allow. Sometimes this means 45 minutes, sometimes this means 45 seconds. Regardless of how long my pieces actually end up being, I consistently approach my work with the intention that it will be a durational work. I always prepare to be invested in an action for the long haul.

PF: So, you consider your piece in Chicago durational?

SS: Yes. It challenged the parameters of real time.

PF: Do you consider your Being (small) project to be an active part of the piece you did in Chicago, or is it non-canon?

SS: Being (small) influences all of my work. It was that project that took me to Mexico, and the other places I was channeling in the piece.

PF: Sound has always been a key element of your work, how has it evolved into the form its currently in?

SS: I collect sound in the same way that I use my sketchbook. It is a way that I process and remember a context. In my pieces, I want to reward the curious witness. Soft sound has been a material that I use for this. It’s like when child is having a tantrum or crying… they say that whispering to them will force them to quiet down so they can hear you. This interrupts the act of crying, shifts their paradigm. Soft sound is my way of creating an experience that shifts the audience’s paradigm.

PF: Can you talk about the choice to use nudity in the context of Defibrillator?

SS: One of Joseph Ravens’ inspirations for opening Defibrillator came from an experience where he was censored for using nudity in a storefront art space. I respect that his response to being censored was to take action and create the kind of art space that he would want to work in and is sharing it with other artists. It’s a great example of someone “being the change”. Choosing to use nudity in the windows was a nod to Defibrillator’s story. Seeing a body (especially a nude one) behind glass also conjures ideas around voyeurism, creating dialogues around the role of the viewer and the action of witnessing.

PF: What are you studying? What’s inspiring you?

SS: I just finished curating an exhibition called INSIDER/OUTSIDER that featured artifacts from live art pieces made in non art contexts. I have been looking at a lot of current work that is being made outside of spaces designated for art viewing. I am interested in the interstices between art and everyday life. I have been reading anthropological and philosophical texts on how people experience space, contemporary theories on the new/ modern body and the collective body, and following fitness tribes that advocate for group movement practices that navigate the natural environment. I am also studying Sadhu Ascetic practices and how this informs cross cultural understandings of the body, place and time. Another way teaching has influenced my practice…it has inspired me to read more!

Second Skin, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Second Skin, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Second Skin, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

object used in Second Skin, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

Daniel S. DeLuca

Daniel S. DeLuca is a Boston based artist and Mobius member whose work explores structures and concepts related to globalization, art, and language. His practice draws from a range of both physical and conceptual frameworks as a means for creating art; including site-specificity, performance art, conceptual art, photography, and sculpture. Daniel’s favorite audiences are unsolicited ones, often working in public spaces and in direct relation to local demographics. His work has been shown nationally and internationally in the context of private and public spaces, galleries, and performance art festivals. Daniel is currently developing artistic research projects that investigate semiotics and the creation of new language, and densely populated reoccurring events around the world.

For Rough Trade II, Daniel continued his project, RKSR+CNL. The following is an interview between Daniel and The Present Tense.

TPT: You have an interesting process for making work. Can you describe it and specifically the process you went through for realizing this work?

DD: The work I did in Chicago was part of an ongoing project called the Roaming Kiosk for Semiotics Research and the Creation of New Language (RKSR+CNL). My first decision was to use the context of Chicago and Rough Trade II as an opportunity for developing this project. I also knew that I wanted to create the work in public then give a presentation about the process in the gallery. That was the basic structure that I followed.

One of the benefits of the project form is that it allows for multiple iterations and approaches to a subject. The RKSR+CNL has two distinct parts. The first invites the public to share experiences they feel are unique to contemporary life and creates a pictorial reference for them using tablet technology. The second part investigates tautology, interactivity and reflexivity, and the nature of signs through live actions and visual presentations. As a result, I felt like I had room to experiment in Chicago and I worked with both parts of the project.

TPT: Instead of using Defibrillator as the context for your work, you chose to take your piece all over Chicago. Can you talk about this choice?

DD: I have spent a fair amount of time implementing actions outside of the gallery context. It is what I enjoy and prefer to do, though I don’t disregard the gallery either, I see it as another context to consider. Typically, I use with the gallery as a place for presenting images and documents from actions, and as a venue for discussing ideas around the work. I enjoy seeing other artists make work in galleries, especially ones that have really developed their practice around it. However, I often wonder what most artists would do and how their work would be affected if they made it outside of a gallery context. I like to consider my options for working with spaces. I shop for context. The spaces within the city of Chicago as a whole create more opportunities for me than thinking within the frame of a single ‘gallery’. The world is a gallery!

Audience/viewers are also a consideration for me. I like audiences that are unsolicited. There is a different dynamic at play when you have an audience versus when you have viewers or witnesses. An audience comes with an expectation. A viewer in public has little to no expectation of what they happen upon. The former creates a pressure to ‘make art,’ while the latter positions the work as a question: what am I seeing? Is this art? It rests on the threshold between life and art. Currently, I prefer the latter. I’m also interested in having larger numbers of people see what I am doing. I like being in urban environments surrounded by people.

TPT: What was your favorite interaction from Chicago?

DD: The book stacks at the U.C Regenstein Library were particularly interesting. It was like searching through an analogue internet!

TPT: Do most of the experiences people share with you include experiences with technology? Any other common threads that you’ve noticed?

DD: Yes, many people gravitate towards contemporary technologies when they think of aspects of life that are unique today. I haven’t asked enough people to feel like there are trends I could identify. In fact, only two people shared their experiences with me while I was Chicago. Talk about terrible data collecting!!! The project has shifted from being focused on an aspect of ‘data collecting’ to illustrating a contrast in the relationship between questions, methods, and the practice of research. I like the idea of setting up methods for conducting research that nullify the perceived potential of the work.

TPT: Has RKSR+CNL illuminated specific ways in which language is being changed by technology?

DD: No, not directly. It is a great question to think about and I’m glad that the project at least points in that direction. I think it’s important to get people thinking about these kinds of things. I’m sure there are plenty of people out there who are doing interesting research on the topic.

TPT: How do you feel wearing a piece of technology?

DD: It’s definitely an attention getter and it can be tiring to constantly have peoples’ attention. It would be nice if it was more seamlessly integrated into fashion and easier to control. I think it would take a little of the edge off of the social interaction. On the other hand it’s fun to see people react and to think about wearable technology. I’m interested in the potential of people communicating with others in their immediate environment, people that they don’t know but share a common interest with. Technology has the potential to be a great social mediator in that regard. It also shows us how much we fear social interaction in a public setting. I think it would be fun to see people interacting in their own bodies and voices in addition to the ones that they project through the internet.

TPT: Can you talk about how you felt when someone scanned you? Did you feel objectified? Does that bother you?

DD: No, I wanted to be scanned. It was a social litmus test. I have a fascination with wanting to know about people who I see on the street, wondering what they do, their interests and experiences. It stems from wanting to ask people questions I have about one subject or another. The Internet is a great source for information but human expression and facial recognition is also important for communication. Getting scanned was a highlight! For me it was a sign that people are open to communicating and interacting in new ways!

TPT: Can you talk about the intention behind your actions? Did that intention change once your were implementing the piece?

DD: The action at Millennium Park was simple: standing, photographing, and scrolling with my pinkie for 2 hours (one hour in two spots). The other part of my process was roaming through the city, photographing, and going inside public institutions or retail businesses. I didn’t want to solicit people into the work. I think it would have been off-putting for some people if I had tried to stop them and engage them in something they may or may not have wanted to be a part of. Personally, I think there are more creative ways to approach people and conversations.

No, my intention didn’t changed. I didn’t have a strict approach to it. I gave myself room and flexibility. I wanted to suggest things about technology, communication, and language. I’m pointing at them, trying to understand them through a common use of them.

TPT: During your presentation at Defibrillator, you included some digital collages of images that you have collected. This was new? Do you anticipate continuing in this direction?

DD: I’m starting to think more about how to utilize the images I capture in the process of making the work as a way to compliment the ideas that I’d like to express. Yes, it’s relatively new, and yes, I’ll continue to think about it.

TPT: What are some of your expectations/ hopes of your audience?

DD: It was important to me that viewers in Chicago saw me wearing a tablet computer and using it in a way that was completely different than what they were used to seeing. The people who read through the question on the tablet got something else from the experience. I would hope that they gave some thought to what they felt was an experience they have had that they think is unique to contemporary life. The audience at Defibrillator experienced my work through the presentation. In that situation the audience has an opportunity to better understand my process as well as some of the theory behind the subject.

TPT: Why did you choose to create this work over the duration of 6 days? What is the role of repetition in this work?

DD: It was a way of gaining access to different situations and approaches. I feel like this project has been comprised of many sketches. I’ve given myself permission to experiment with how the content, and subject take form. The duration also gives more people access to the work.

TPT: Were there any moments that surprised you?

DD: I was surprised when I found Cloud Gate as the site for another action. It was too appropriate to pass up.

RKSR+CNL, 2012, photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

RKSR+CNL, 2012, photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

RKSR+CNL, 2012, photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

RKSR+CNL, 2012, photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

RKSR+CNL Lecture Performance, 2012, photo by Sandrine Schaefer

RKSR+CNL, 2012, photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Philip Fryer

Philip Fryer is a Boston based artist who explores concepts of mortality, chaos and order, the body as a circuit, and the omnipresence of sound. He works primarily in performance but also utilizes noise, video and installation in his work. His recent exploration has been focused on using lo-fi technologies such as circuit bending and cassette tape loops, both as individual pieces and as elements of performances. Philip is a co-founder of The Present Tense, an initiative that has organized 10 performance events since 2005 and has exhibited the work of over 200 artists. He has exhibited his work at The Darling Foundry (Montreal, QC), Grace Exhibition Space (New York, NY), Vertigo Series (Cedar Rapids, IA), Idyllwild Arts Acedemy (Idyllwild, CA), DEFIBRILLATOR gallery (Chicago, IL), The Museum of Fine Arts and 100 Years of Performance Art (Boston, MA). He as also been a member of the boston based dark ambient project TOOMS since 2012, and performs under the solo moniker Moondrawn.

In addition to co-curating Rough Trade II, Philip created TREE/POOL/SKY 2012. The following is an interview between Phil and Sandrine of The Present Tense.

Sandrine Schaefer: How did the context of Defibrillator impact this piece?

PF: Since sound is such an essential part of this performance, the noises I found within the space really dictated how the piece was performed. The movable walls and the metal attached to the wall helped to lay out how and where I did each action.

SS: What was your inspiration for this piece?

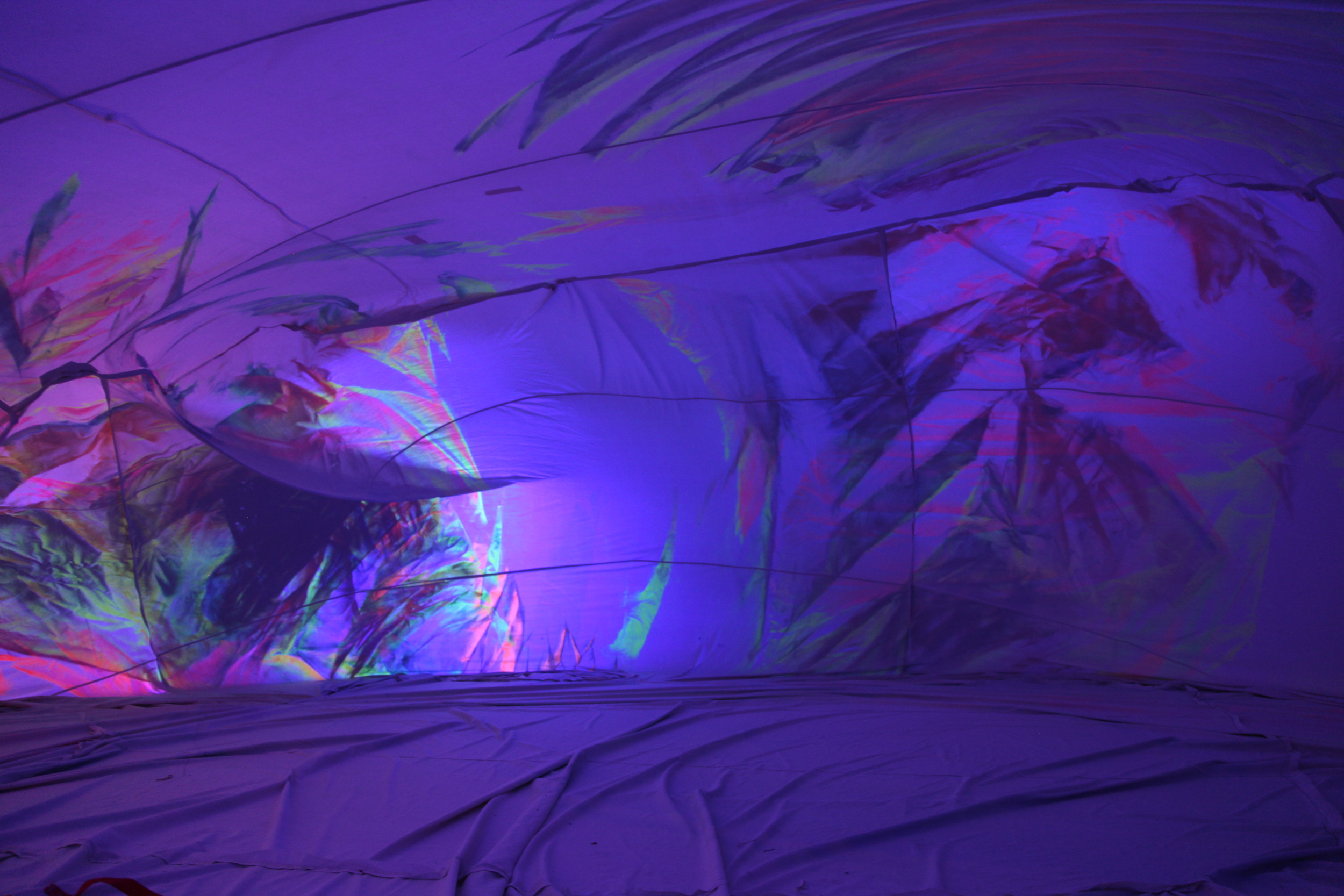

PF: The lyrics of a Mount Eerie song titled “Summons”. It’s about a pool of water formed by the roots of a tree being pulled out of the ground when it fell over, reflecting the image of the sky. The visual of this in my head made me think about how these things are seemingly separate, but at that moment are connected. I aim to do the same in this piece, to find hidden things within a space and imagine what else might lie behind walls or under the floor.

SS: This was the 3rd version of TREE/POOL/SKY. How has it evolved?

PF: The first version in Boston was much more paired down, partially because it was in a small space. It felt unfinished so I decided to perform it again. A few months later I was in Montreal, where it really took on a life of its own. Many actions were added in that version, including sounding the space, peering at audience member through the black portal, and recording and playing a cassette loop live. I had anticipated doing the same actions as I did in Boston but once the performance started I felt the piece wanting to fill the space (which was enormous). The third version in Chicago didnt really see any actions added, but they certainly altered based on where I was and who I was with. Rather than interacting with audience members I didn’t know like I did in Montreal, I chose to acknowledge people I did know (Sandy Huckleberry and Marilyn Arsem). Marilyn was the first person to take the interaction a step further and put her hand through the portal and touched my lip. I can’t explain why, but this interaction makes me feel like this performance is now complete.

SS: Can you elaborate on the sound that was present?

PF: I like to think of it as a heartbeat. A heartbeat generated by the space that is unique and omnipresent. It is one of a million possibilities.

SS: Talk about portals…

PF: This is a new element to my work that is yet to be really explored. I have a feeling that the next things I work on will delve further into what a portal is to me. In TREE/POOL/SKY, it is simply something that can swallow a being or alter its form.

SS: Can you talk about the intention behind your actions? Did that intention change once your were implementing the piece?

PF: No, the piece has stayed pretty true to what I set out to do. It’s the first time that I’ve had an idea that I’ve felt the need to explore until it feels completed by performing it several times.

SS: Can you talk about the extension?

PF: The extension came to me more as a visual than as an idea. I really liked the image in my head of a body extension that erases identity and creates something that looks almost non-human.

SS: What did it feel like to engage in such an intimate action with the audience (eye contact through the portal) then to be cut off from them? When you couldn’t see or hear were you scared or did you feel that that first action cultivated a sense of safety in the space?

PF: I like the idea of an experience transforming over the course of time. Initially, this experience with the audience is an intimate one and only a few have it, which makes it kind of sweet. Later in the performance, the portal changes its tone and takes away my senses. It was very scary in this performance, however, I did a different piece titled “APOCRYPHA” there I stood on the edge of a shipping container for 3 hours wearing the extension. It was really scary because I was only a few feet away from a 10 foot drop, and the sensory deprivation made it so that I could tell how close I was to the edge. That was pretty scary.

SS: Talk about Xfiles and John Cage.

PF: I recently came out of the closet as an x-files nerd. It’s really had a big impact on my work. I just really enjoy the fact that each episode is its own rhetorical question, and challenges the viewer to question things in our realities that we take at face value. I wish they had done an episode about John Cage, that would have been awesome.

SS: What are some of your expectations/ hopes of your audience?

PF: I really just hope that the audience gets something out of the performance. I hope what I’m trying to convey is coming across but I really like hearing interpretations as well. Marilyn push my expectations a bit because I don’t get a lot of unsolicited interactions with my work, and it was really nice to have that happen. It really makes you check in with yourself about what your doing and how your doing it. If someone is moved enough to interact in an unexpected way it forces you to evaluate why it happened.

SS: How was performing in Chicago different from making work in Boston?

PF: It’s always something I think about when I don’t perform in Boston, that different cities have different influences and histories. Therefore, your work is going to be read via that lens.

SS: What imprints did Chicago leave on you?

PF: The most American city I’ve ever been in. Looking at the Sears tower from an empty lot. Triumph and tragedy.

SS: What is inspiring you at the moment?

PF: Lucky Dragons “Ouija Miore (A Wave That Interferes)” synthesizer. An interactive, sonic and visual synthesizer that utilizes both chaos and order.

SS: Any words of wisdom?

PF: “If you understood everything I said, you’d be me” -Miles Davis

TREE/POOL/SKY, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Marilyn Arsem

Marilyn Arsem has been creating live events since 1975, ranging from solo performances to large-scale interactive works incorporating installation and performance. She has presented her work in 27 countries throughout Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and North and South America. She is a full-time faculty member at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where she teaches performance art, and is a graduate advisor. In the past fifteen years, Arsem has focused on creating works in response to specific sites, engaging with the immediate landscape and materiality of the location, its history, use or politics. Sites have included a former Cold War missile base in the United States, a 15th century Turkish bath in Macedonia, an aluminum factory in Argentina, and the site of the Spanish landing in the Philippines. For Rough Trade II, Marilyn Arsem created, still.missing, 2012. The following is an interview between Marilyn and The Present Tense.

TPT: How did you find performance art? How did performance art find you?

MA: I think it found me… I remember being completely taken by written accounts of Happenings when I was in high school, and as a result we created our own, a group of us collaborating and combining different media. I remember even then being interested in real time rather than in narratives, in actions with materials rather than in plots, in visual images rather than in characters, in engaging with the audience rather than building a fourth wall. So it made sense to align myself with the visual and performance art and new media communities.

TPT: You have an interesting process for making work. Can you describe it and specifically the process you went through for realizing this work?

MA: I try to follow certain instructions to myself:… to do something that I have never done before, to work with the specifics of the space, to consider the context of the event, to make use of what is easily available, to not make unreasonable demands on the institution hosting the work, to tread lightly and leave no marks, to operate from my current state of mind, to pay attention to what I am paying attention to, to not be afraid to fail. I remind myself that I am not obligated to entertain the viewers, that I can ask questions rather than provide answers, and that all I can really do is respond to what I am encountering at that time, from where I am in that moment. It is a conversation, an inquiry, a process of discovery, rather than a statement or position.

TPT: How did you arrive at the decision to work in Defibrillator’s windows? How did this context inform your piece?

MA: I hadn’t expected that the windows would be available, since I understood from the website that they were curated separately. So it was only when I arrived on Thursday night that I heard that it was possible to work in them. I was especially interested in the fact that the audience moved in and out between the two windows; that there were actually two separate windows to use.

TPT: Can you talk about the flour?

MA: It was a practical choice – I wanted the floor to be as white as the walls – I suppose I was influenced as well by the floor of the gallery being so newly painted white. But really I just wanted the visual of white. Later I thought that it suggested snow or clouds. And I knew that flour would be easy to get in quantity, as I was told that there was a grocery store nearby… and finally, I knew that it would be relatively benign to lie in it.

TPT: Can you talk about the blue chair?

MA: The choice of a chair descending occurred in stages. First I thought of something rising, but then decided that something descending would be a better choice. I am not sure why I decided that, though I could say that I have done a number of works where some object has risen into the air, and so I thought doing the reverse might be interesting. And it felt right…

Then the question was what should descend. Fruit? Shoes? Nothing seemed right. Sabri, an artist who used to live in Boston, but is currently studying in Chicago, suggested ‘furniture,’ and then I thought – of course, a chair. Choosing the color took longer, but then light blue seemed right. Later I thought of it being a reverse sky…

A chair might be considered a body, or something waiting to hold another body… Or the descending chair might be read as ‘Deus Ex Machina.’ However, when the chair arrives it is empty. Still waiting. Something is missing.

But these choices – white, flour, chair, blue, are really just intuitive choices. My understanding of them, or explanation of them, comes hours or days later, and most often in reflection on the work, after the performance happens.

TPT: Is there a relationship between these objects and the broader scope of your work?

MA: I am not sure how I might answer this question… I have had chairs in performances before – a small red chair high in a tree; a chair made of ice in which the audience sat; a red chair placed daily in the landscape to witness sunrise… I consider an empty chair as a very interesting site – an offer, a place waiting to be occupied, or evidence of something or someone who is missing…

TPT: Can you talk about the intention behind the actions? Did that intention change once your were in the piece?

MA: I don’t think that I have a way to talk about intention. I had an image of myself lying face down, in white. And so I created that. I wanted to be lying down, not engaging with people. But I did want something to change, to arrive, to offer some other possibility, even though it was unfulfilled.

TPT: What were you thinking about during your piece?

MA: Haha, well actually I was trying not to think about how painful it was, how I wished that I had made a test for myself about what might be a more comfortable position to occupy. But, I also had wanted to simply land in the window, on the flour, as if I had fallen from the sky. And so that is how I ended in that position – I more or less fell into it.

TPT: Where were you during your piece?

MA: Breathing. Listening. Lowering the chair.

TPT: What were some of your expectations/ hopes (if any) of your audience?

MA: In this context I had many fewer expectations of the audience than usual. In my mind, I was simply an image that slowly transformed over time. I wanted them to see me, to forget about me as they watched other performances, and then look again to see the chair slowly descending.

TPT: How was performing in Chicago different from making work in Boston?

MA: I rarely make work in Boston. Being in Chicago was a pleasure, not the least being that I spoke the same language as the residents. I could anticipate how they might view the image. Oh, and I could find my materials more easily, negotiate paying for them with ease…

TPT: Can you talk about the process of titling your pieces?

MA: still. missing

My computer resists that title, trying to make the S and M capital, or change the period to a comma. It resists, trying to follow rules…

But choosing a title happens for me after the work. It is a way to give a clue to a way of thinking about or looking at the work. More information. And so in this case I am trying to accurately identify what was happening to me at the time, and attempting to name that experience, or at least suggest other information in order to have a more in depth reading of the work.

still.waiting, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

still.waiting, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

still.waiting, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

still.waiting, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

Jeff Huckleberry

Jeff Huckleberry is an artist and educator living in Boston and has been performing art for the last 20 years, both nationally and internationally. He is a member of Mobius Artist Group and is the Artistic Director of TOTAL ART. He enjoys the bicycle, the hammer, the saw, the wood, his wife and son, his family, his friends, his work. (…except sometimes he doesn’t enjoy these things as much; it depends.) He is the son and grandson of far more practical people, which he tries to express in his art. Some people say he is more handsome without his glasses, and his mother thinks it is time to stop getting naked in front of people. Oh, and something about death.

For Rough Trade II, Jeff Huckleberry created Fourth Rainbow, 2012. The following is an interview between Jeff and The Present Tense.

TPT: We’ve interviewed you before when you had a show at MEME, what’s happened in your work since then?

JH: I’m not sure. That was a few years ago so everything has changed and everything is more or less the same. Clowns are new, and so are making rainbows. Actually, I think all of the colors I am thinking about and using now come from that show.

TPT: Why Rainbows?

JH: Again, I’m not really sure. These started when I went to Marseilles last year. On the way over, I started thinking about rainbows and the color wheel, and the pursuit of the unattainable. From the very first time I tried to make one (a rainbow) it hurt me; or at the very least it hurt to make it the way I was trying to make it, and I thought that that was really interesting and powerful. Of course I like the failure/success aspect of the attempt, and I am surprised each and every time I try to make one. I “made” two rainbow performances in Marseilles and the second one found a purpose. My location for performing was this big broken fountain in the middle of this really busy, small little square. I wanted to christen the fountain as the fountain of the artists, (the fountain didn’t work, which I thought was appropriate.) so I wanted to try to make it work again. I believed so hard in that piece, and in the power of each color, and in the end I think I got the fountain to work just a little. That was the first time I felt the alchemy of the rainbow, which intrigued me even more. As for what they mean, or “why” I am interested in making them, I don’t really want to know right now. It is a process of discovery, and each time I do a little research on rainbows it leads me down some other interesting performative path. I do like many things that have happened; like the little rainbows I made emerging from piles of dog shit on the street, or the way the one rainbow managed to eat the finish off of the floor at BU, and how funny the last one was in Chicago. That was really enjoyable. Funny is becoming more important as well.

TPT: You used smaller planks in this performance, why?

JH: Shoulder shrug. Smaller than what?

TPT: Do you feel that humor is an important part of your work and why?

JH: Yes! It has become more important lately, especially after a collaboration with my friend Julie Andree T. We did a performance together called Two clowns and a death, in which we tried to “die” in as many different ways as we could. I really got to be a clown for the first time and it was wonderful. It just made so much sense. My wife and I did a series of performances last fall that was using one color of the rainbow for each night of performance. It was amazing how each color really effected the actions we did and our relationship to each other. ( I think 3 people total saw those performances. Now that’s funny!) We both had a great time working together and the performances were very often funny, and we laughed at each other through many of them. I like the way it opens a door to and for the audience. In fact in Chicago I was trying to ask audience members to go out on a date with me – like let’s get to know each other here, but this is completely awkward. After all, I am going to be naked in front of you, and I am going to compromise and embarrass myself so we are going to have to get to know each other pretty quickly in order for this to succeed.

TPT: What were you trying to do when you were writing on your body in this performance?

JH: In this instance I was trying to ask the audience out on a date. In other performances it has been a one sided conversation with someone in particular; my uncle Douglas, some kid who went to the high school I taught at, my mom etc.

TPT: Can you talk about the choice to have one empty chair that you treated as an audience member?

JH: That chair is for Bob Raymond. I might as well give him something to do, maybe he’s bored.

TPT: Have you considered patenting your tightie whitie tool belt idea?

JH: Uh, there is a patent ©HUCK

TPT: That was a cool hammer. Not a question just saying. Anything else you would like us to know about this piece?

JH: That would spoil the fun

Fourth Rainbow, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Fourth Rainbow, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Sandy Huckleberry

Sandy Huckleberry has been a performance artist and curator in Boston, MA for many years. She is currently a member of the Mobius Artists Group and was a member of TEST performance. She grew up in Greenwich Village in New York City and received her art education at Smith College and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She has performed in various locations in the world.

For Rough Trade II, Mothergirl created Fishing, 2012. The following is an interview between Sandy and The Present Tense.

TPT: Your last few performances have been collaborative but this one wasn’t, how does your work change when its just you?

SH: I think my response in collaboration is a little like when I’m talking to someone with a strong accent and I just can’t help but start falling into the rhythm of that speech and doing it myself a bit. Either that, or I become a little more intensely the opposite of whatever’s happening. When working with Jeff, for example, I tend to get a little butch. Working with Mari, I tend to react to her intensity and slowness by becoming very quick and flighty. Working with her recently brought this to my awareness. I was almost like a dog shaking off water, trying to get through the task of the performance so quickly.

When I first started performing, almost 30 years ago, I had such a self-assured sense of “presence” (from being a dancer, singer, actress, etc.) that it kind of annoyed me. It almost seemed hackneyed, or something, so I wanted to throw it away. I oriented my work toward doing tasks, and got used to talking to the audience as if I were chatting with guests in my kitchen while I cooked. Working with Mari, and then seeing your performance at Defibrillator, I realized that (in comparison to your sense of presence) I had thrown my own “presence” so far away that it had gotten lost and it almost seemed like I’ve been hurrying through performances to get them done, as if they were the slightly less interesting items on a long to-do list. What they really are is a sacred opportunity to come into communion with myself and others. So I wanted that back, and for this performance I decided to give myself the time to try, and quite possibly fail, to do something almost impossible.

When I’ve just been working with others, and then work with myself, I’m still resonating to a sense of challenging/emulating an “other”, and so I think I look for the “other” in myself. This particular performance, I was trying to figure out some aspects of a recent experience that were obscure to me. So I was searching (or “fishing”) for something to be learned, something I knew was there but I couldn’t figure out.

TPT: You mentioned this performance came from a childhood ritual, can you tell us about that?

SH: When we were kids, my mom used to make this game for my sisters’ and my birthday parties. She would hang a sheet over the chin-up bar that spanned the doorway to our bedroom, and each kid would hold a “fishing rod” (a stick with a string attached) and “fish” over the sheet and pull over a little treat or toy of some kind that they could keep.

TPT: It was quite a difficult task to catch an object, was it that difficult when you were young?

SH: Not at all. My mom was on the other side, tying the treats onto the string!

TPT: You had two distinct parts of this performance, one part on the ground with your objects and one above. Can you tell us about why you chose to have two different approaches to the same action and what they symbolized to you?

SH: Well, I think this goes back to the sense of searching for something. I needed an alternate place to get a perspective on what I was searching for. I didn’t know whether the forest or the trees would be more helpful. In the end, it was the forest.

TPT: Many of the materials used in this piece were things you got while in Chicago, what went into the process of choosing what objects you wanted to use?

SH: Well, I went into the thrift shop open to what I might find. I was looking for things I might, or might not, be able to catch on my hook. (Practical.) Other than that I just found things that I might be interesting to look at, or catch the light. (Formal.) I also hoped there might be some things that would resonate with me ( I found some goblets that reminded me of my grandmother) and some things I really disliked (a detached, broken plastic holder for speaker wire with a bit of wire trailing off of it). (Content.)

For the stick and stones, I went foraging on a lovely walk in a park and around the neighborhood. That’s always a huge pleasure for me, and an important part of the performance.

I borrowed the string.

I purchased the wig (my one “souvenir”).

“Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.” Good for weddings, good for performances…?

TPT: Why the blue wig?

SH: That was actually the first clear image I had for the performance. Although I brought the emotional content of the performance with me, I waited until I got to the space to figure out the particulars of the action. My eyes were drawn upward (such wonderous high ceilings) and I saw the corner of the partition, that looked like I could climb up there. I got an immediate picture in my head of wearing a blue wig and looking through binoculars down at the crowd. I liked the sense of distance the wig gave me… distance from the “other” me that was toiling down below. I guess the wig was “she” (the forest) and the one below was “me” (the trees). If I think about it now, where that image came from, I guess I think of two things.

One is that the idea of being up above the crowd, on that little partition in the corner, makes me think about an experience I had when I was about 15. It must have been 1978 or 9 and I was at a club in New York with some friends. It might have even been called the Triangle club. It was a tiny little place, a loft in the shape of an isoceles triangle. 60 feet at its longest, with a teeny stage in the sharpest corner. We’d gone there to hear an electric violinist called “Nash the Slash”. I guess it was what would now be considered a hipster place, because I remember Debbie Harry was there (she threw up in the elevator, as I recall) and so was David Bowie. He took a turn with the DJ, who was perched in the dark above us all on a tiny little platform at the top of a very similar partition against one wall, and began spinning tunes of his own choice for us all to dance to. Great memory. (I loved to dance!)

Anyway, the second thing was that I saw “Moonrise Kingdom” this summer and the girl in it reminded me of me at that age. Really into dressing up and being somebody else, somebody who wouldn’t be caught dead in the time and place in which she actually found herself.

So, yeah, I think that’s why the blue wig.

TPT: Is there anything else you’d like us to know about this piece?

SH: Jeez! I’ve already said a lot. I never write this much about a piece! Mostly, I just do them and then they’re done. I sometimes tell people about what happened, if they seem interested, but that’s it.

I will say that I was able to feel more present and less rushed than I have in a while. Maybe it was because Marilyn’s piece was durational and Daniel’s was brief and in a “lecture” format, that I felt I had the opportunity, or even the responsibility, to take my time and allow the piece to be a longer one. The crowd was very kind (by which I mean attentive and enthusiastic) and it was only after that I worried I might have bored some people. (That’s always a speed-inducing thought if it occurs in the middle of the performance.)

So maybe I did find some of the elusive stuff I was fishing for…

Fishing, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

Fishing, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

Fishing, 2012 photo by Sandrine Schaefer

Joseph Ravens

Joseph Ravens creates time-based art works that encompass text, movement, installation, technology, costume, and object. He completed his undergraduate degree in theater at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater; studied audio/visuals at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, Netherlands; and is a graduate of The School of the Art Institute of Chicago with an MFA in Performance Art. Over the past decade Ravens has presented his work at international festivals throughout Asia, Europe, South America, and the US. He is a recipient of the Illinois Arts Council Fellowship for Interdisciplinary/Performance Art, and the Illinois Arts Council Fellowship for New Performance Forms, as well as other grants and awards from state and city institutions that have allowed him to foster an international reputation. Founder and Executive Director of DEFIBRILLATOR performance art gallery, Ravens was recently named a 2012 New City Breakout Artist.

In addition to co-curating Rough Trade II, Joseph created Mastication, 2012. This is an interview between Joseph and The Present Tense.

TPT: How has being an artists influenced your curatorial work and being a curator influenced your artwork?

JR: As an artists who has participated in many festivals and exhibitions, I’ve seen a lot of work. I’ve seen it from the inside. So I’m familiar with many styles and aesthetics and have a sense of what is commonplace or unique in the industry. I understand an artists needs and when putting together a project I am able to interpret and more accurately fulfill an artists vision. Basically, I want to make it as easy and painless as possible for the artist to present their work – free of unnecessary burdens or limitations (as much as possible). Also, again in a practical sense, I have met a lot of amazing artists over the years and I have been able to call upon these resources and connections. Defibrillator aims not only to support local artists, but to invigorate the local art community by bringing international and out of town artists to Chicago. My history as an artists has helped make this possible.

In terms of how curating has influenced my work, I think of two things, First, I’m being exposed to much more work that ever before. I see a large number of performances and learn great deal from each and every one of them. This has refined my sensibility. I am able to envision and more accurately predict how a project might be perceived by a viewer. I notice trends and tendencies and human behavior and this awareness had filtered into my work. Secondly, my time is less fluid now that I’m administrating. So whereas in the past I may have spent a lot of time preparing and building a performance, now my work is more conceptual and DIY. I’ve embraced an aesthetic that is a little less perfect or labor intensive. I relish working outside my comfort zone and have enjoyed the fear and risk that are present as a result of working in this way.

TPT: Do you have an ideal context that you like to make work in?

JR: No. Does this answer surprise you? I really enjoy contextualizing and recontextualizeing work to discover who it changes based on environment and modes of experience. What happens when I take a performance that was designed for the street and reinvent it for the gallery setting? What happens when I take a duration installation-baed work and show it in a theatrical venue? I’m curious about these questions and find pleasure in re-presenting work in various situations.

TPT: Can you talk about the role of the personae in your work?

JR: I am myself in all of my work. Perhaps hyper versions, alter egos, or latent aspects of my self, but still me just the same. So even if I am embodying a giant lizard, I am still Joseph – just a primordial version of myself – myself in another diminution, perhaps. Certainly, my theatrical training has left its residue in my work, but I don’t think of my personas as entities other than myself with other motivations and other objective. Optimally, these characters are not only reflections of my self but the also embody aspects of humanity that the viewers can relate to and, possibly, recognize in themselves.

TPT: In Mastication, you “regurgitate” a line of kale leaves. Can you talk about the intention behind this action? Did that intention change once you were in the piece?

JR: It’s funny how things evolve. I was asked to create a performance for an exhibition called “Flip/Flop”. The idea was to have work that started as one thing and then became another: transformation. As is often the case, my body is the primary site for research and experimentation so I started thinking about how my body can change something, like food to shit or water to urine. I didn’t want to go there for this work, but began thinking oaf the mouth (and digestion) as a means to transform something. I actually made the tail for another project – one about evolution that embraced ideas I was having about vestigially. But I didn’t like that project and the costume was sitting unused in my studio. so I made ver fast, practical choices. In my work I often limit myself in some way – I cant move or I can’t see, or I can’t breathe. I knew I wanted to keep this element, but the costume wasn’t really restrictive. So I started thinking about the little arms that a Tyrannosaurus Rex have – that they are basically unusable. I decided not to use my hands for the performance. The intention didn’t change, necessarily, when I was in the piece, but because the kale leaves were closer to the floor, I had to use my hands to support my body when I bent down to chew them. I think my intention remained the same, though, it was just modified or adapted to fit the situation. Often I am inspired by nature or natural things. When I begin putting this work together I remember thinking about going to the zoo and watching animals eat – relating to them on this basic level and considering how it was similar or different from my own eating experience. This was the simple intuition behind the work and it was consistent throughout the performance.

TPT: What were some of your expectations/hopes (if any) of your audience?

JR: Gosh, I don’t know that I had any. I guess I always hope that I engage the audience. I worry that they will get bored when I show very minimalist work that isn’t very dynamic. This work was very linear. There were very few (if any) peaks and valleys. I’m a generous performer, but as I get older ad more seasoned, I just trust that this will happen. Or, perhaps, I don’t care as much if it does.

TPT: Were there any moments that surprised you?

JR: Yes, I’m always surprised about how difficult it is to chew for that long. Kale is quiet fibrous, so it was a little more work than I intended. I was sweating like a pig!

TPT: How was performing in Boston Different than making work in Chicago?

JR: I don’t think there were many differences in terms of geographical region. However, the large venue (The Pozen Center) was a challenge and it was interesting to see performance situated in such a massive space. The audience had to determine their physical relationship to the work- how close or far to be from the artists. This was interesting to me on a behavioral level.

TPT: What imprints did Boston leave on you?

JR: I have a perception of Boston as an intellectual city, and certainly, I feel that the students ad artists I interacted with were very smart they think about their work. I appreciate that. I don’t know if I can accurately make this assumption, but I feel like Chicago artists might be more visceral- producing something that comes from impulse or instinct. I felt like the Boston artists and the students were really contemplating their work- they were thoughtful. I felt like they were eager to learn and experience something. I felt a sense of community surrounding performance and found it exciting.

TPT: What is the role of repetition in this work?

JR: I was thinking more about minimalism, but now that you mention it, repetition is often present in my work. I think it represents life and labor. Every day we brush our teeth and go to work and do the same thing every day. Repetition is life.

TPT: Did you fabricate the lizard costume? What is the role of sculpture in your work?

JR: Yes, I made the costume. I’m always interested in modifying my body, misshaping it and playing with proportion. Objects and sculptural costumes often limit my mobility or senses in some way- they often serve as restrictions. This, too, is a comment on life. I’m curious about how we can prosper or thrive in situations where we are limited. I’m also interested in impact and seductions. Sculptural elements are integrated in an effort to lure in the viewer. These elements give them an access point that has a visual appeal so that they might stay a little while in my little world and reflect on what I might be trying to communicate.

TPT: Can you talk about the role of the grotesque in this piece? What about humor?

JR: I’m interested in that place between the grotesque and humorous. I think the line is very thin. Early in my career, I noticed that people saw humor in my work. I didn’t try to insert it, it just happened. So now, I embrace it. I think my fondness for the grotesque or strange imagery comes from my appreciation of Butoh. I’m interested in moments and things that are strange in a sort of anthropological or psychological way – how we react when we are confronted with this sort of imagery. For me, humor is a coping mechanism. I’m inspired by my own experiences when I see something weird and I laugh because I don’t know what else to think or do in that moment of discomfort. I enjoy mystery and relish an opportunity to make the viewer wonder.

TPT: What is inspiring you at the moment?

JR: Fitness…America’s obsession with being lean, strong, and attractive. Vanity and sacrifice. Devotion and Dedication. Work and transcendence in regard to physical exercise and how this relates to performance art.

TPT: Who/What is influencing your work presently?

JR: I am really interested in young/ emerging artists. I’m looking at the choices they are making and wondering why they are making those decisions. Young artists are in tune with popular culture or possibly, a particular subculture. I’m looking at these young artists’ work and thinking about where it is coming from- what impulse are they responding to- what aspects of our culture they are influenced by and are thus representing. I’m looking at a lot of proposals and a lot of artists’ websites so I am influences a lot by other artists and more so, how they are representing their work.

TPT: Any words of wisdom?

JR: I noticed a transformation in my work when I began to make things that I wanted to see rather than work that I felt others wanted to see. I make performances now for myself, to satisfy my impulses to make images or actions come to life. I still consider the viewer, of course, but this takes a back seat. I don’t know if the work is stronger now, but it comes from a more interesting place. This quality is tangible and lends the work a texture that wasn’t there when I was creating perfromeacnes that I wanted others to “like”. I have found that if I like it and feel a connection to it, the work will resonate and be well received.

Mastication, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Mastication, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Mastication, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Mothergirl

By creating theatrical events in non-theatrical spaces, Mothergirl (Katy Albert and Sophia Hamilton) combines the use of complex contextual framing with a hypersensitivity to discovered and assembled setting. The style of their work ranges from installation to interactive performance.

For Rough Trade II, Mothergirl created What you Look Like, Too, 2012. The following is an interview between Mothergirl and The Present Tense.

TPT: How did you find performance art? How did performance art find you?

M: We are both studied theatre in school, but when we started working as Mothergirl, our ideas started moving farther and farther away from the definition of traditional theatre, and we realized that we were doing something else completely.

TPT: How did you meet? How long have you been making work together?

M: We met in college in 2005. We started working together in a found space experimental theater company, Balls Deep Theatre Theater in 2007. It began as the most tentative friendship and transformed into the strongest one either of us has ever formed. We have tremendous power over each other.

TPT: Can you describe your process for collaborating?

M: Painstaking! Our ideas evolve out of a lot of pointless discussion with occasional moments of clarity. We joke a lot, then we tell ourselves to get serious and make work. There is a long stage of building our objects and during that we have a lot of time to enhance and fine tune the idea. Frequently the objects we build inform the performance as much as the idea does. Most performances we do are the result of (at least) a month of gradual work.

TPT: How did the context of the Pozen Center inform your work?

M: We had to consider what the piece could look like in a gallery setting and how to get isolated audience attention in that context. Something that was visually arresting from afar and from inside. The largeness of the room definitely affected the way that we were heard when we spoke.

TPT: You had performed What You Look Like before for Out of Site Chicago. Can you talk about this experience and how it informed the version created for Rough Trade II?

M: When we performed What You Look Like at Out of Site, the audience had to stick their head into a large freestanding box in a public place, one at a time, and we performed separately from each other (in two different boxes). In the context of a gallery, we didn’t think the boxes would be as effective as the viewers were already aware that it was a performance event. Mirrors and reflection are a big part of the piece so we decided to physically represent that theme. Audience risk and payoff is also very important to us. In the Out of Site performance, the audience had to risk their personal safety by sticking their head into some mysterious room, but in end their curiosity was rewarded. For the Pozen Center, the audience had to be the center of attention in the performance, and by doing that they got to sit on the pillow, hear what we were saying, etc. In both we found the pictures to be a big incentive.

TPT: How did you decide on the words and images that you used in this piece?

M: We wanted to create a home for the characters, which is why we made the nest. We wanted the pillow so it was clear for the audience that they should sit. The words were chosen to be approachable and funny, like “woah” and “yeah”, but also to be sort of blank and contextless to further the naïve nature of the flower beasts.

TPT: Your synchronized whispering was impressive! Did you have to practice a lot?

M: Our work uses a lot of unity and synchronicity in different contexts, so we’re used to it. We are also quite familiar with each other’s speech patterns in daily life as well as in performance, so it was relatively easy to match cadence and tone. We tried to anticipate possible responses from the audience, so that we could react in unison, but there were a couple of instances where we were caught by surprise!

TPT: Did you feel like you were the same flower creature when you were in the performance?

M: Yes. It felt a little like a trance.

TPT: Can you talk about the intention behind the actions? Did that intention change once your were in the piece?

M: We were trying to channel the feeling of the moment when a person realizes that they are a subject, and that the rest of the world, including their own image, is impenetrable to them. It’s magical but also a little scary. Actually, the intention felt even stronger in performance than when we were just talking about it.

TPT: What were some of your expectations/ hopes (if any) of your audience?

M: We expected the audience to be patient, and to adopt the same pacing in their actions and thoughts as the Flower People. We expected people to follow the implied rules of the performance, (sit, speak nicely to the Flower People, etc.). These expectations weren’t set to control the audience member, but to guide them to the small revelation of self that we set up when they have to sit and watch their own image appear in the instant photographs.

TPT: Were there any moments that surprised you?

M: Because we were mirroring, we had to follow each other’s movements, which led to some fun discoveries, like fluffing the pillow, which looked amazing and we seriously could have done for hours.

TPT: How was performing in Boston different from making work in Chicago?

M: We were struck by how so many of our experiences during our short time in Boston were affiliated with institutions of higher learning. Neither of us went to school in Chicago, and the majority of our performances there have been outside of colleges and universities.

TPT: What imprints did Boston leave on you?

M: It felt very safe, there was a great coop, really wonderful people.

TPT: Why did you choose to create this work over the duration of 3 hours?

M: Only one audience member at a time can experience the work, and our goal is to encourage participation, so we stayed as long as there were people interested in participating.

TPT: What is inspiring you at the moment?

Katy: The house I just started renting, it is huge and falling apart. I keep relating it to those dreams where you are in a room or a place that you are very familiar with, but then you discover another room inside of it, and you’re like, “Oh! This room would be perfect for_______!”. I really like fashion blogs, and find them a bit more inspiring than art books, mostly because I think fashion shows are often about world creation and storyline. I am very into persona musicians, and the concept of persona in general—which is probably why I am also really into trashy two-dollar magazines and reality television.

Sophia: Social justice issues in urban education; online drag makeup tutorials; dada; nail art; Adam Rose; the Cauleen Smith: A Star Is A Seed exhibition that was recently at MCA Screen—it included a mirror maze; Real Housewives of anywhere; Twin Peaks/Blue Velvet (always); the Fall slip into dreary weather; Buckminster Fuller’s geometry of spheres; thinking about what I would say to Rahm Emmanuel if we got to talk; cats with human emotions.

TPT: What are you studying?

Katy: I am teaching myself the guitar, which I attempted once when I was very young and gave up too quickly. I am reading about psychedelic art and pairing that reading with novels that have some loose connection. Incidentally, I am studying household maintenance, which has a lot to do with the new house and my desire to take a warmish shower.

Sophia: Currently reading: The Transformative Power of Performance by Erika Fischerlichte; A Year From Monday By John Cage (on loan from Phil!); Catching the Big Fish by David Lynch; and The Other Wes Moore by Wes Moore. Learning to speak Greek. I’m also making a bike generator, which is proving to be a steep learning curve in electronic components!

TPT: Any words of wisdom?

M: We’ll share with you our personal collaboration mantra. It’s helped us through some rough times. Okay, here it is:

Hype up when you get down.

What You Look Like, Too, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

What You Look Like, Too, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

What You Look Like, Too, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

What You Look Like, Too, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Meredith and Anna

Meredith And Anna are former roommates who have been curating shows as the Happy Collaborationists since 2010. They have recently started orchestrating performances, which consist of meticulously planned simple actions with extemporaneous reactions to the resulting situation... these are their best ideas.

For Rough Trade II, Meredith And Anna created Red Flag, 2012. The following is an interview between Meredith and Anna and The Present Tense.

TPT: How did you find performance art? How did performance art find you?

M: I signed up for Performance Art I thinking I was taking an acting class, I had been involved in a local improv group. My performance art professor Mat Wilson (Industry of the Ordinary) was quite dissatisfied with this historical perspective. Performance art found me when, once educated by Wilson) I started inserting my work into the public sphere and was uncharacteristically embraced by the public for the medium.

A: I’m pretty sure I have always made performance art. I just didn’t know what I was doing until I started working with Industry of the Ordinary. In high school I would do things like hook up a Karaoke machines in the car and drive around picking up people to sing with my friends Kyle and I. I went to art school as a painter until I found I could approach activities I already love, like singing Karaoke in the car, aesthetically and construct artistic experiences.

TPT: How did you meet? How long have you been making work together?

A: We met eating take-out from Sultans Market on the floor of the Happy Collaborationist Exhibition Space. Meredith was a part of Before Cake, After Dinner - a performance art group that we exhibiting showing at Happy C.

M: I feel like it’s important to note that I hate everyone upon first meeting them but in the same breath I am capable of falling in love. I fell in love with Anna and Hadley of the Happy Collaborationists … they also let me smoke inside.

A: Meredith joined the Happy Collaborationists curatorial collective three years ago and we have been collaborating on our artistic practice together for about a year.

TPT: Can you describe your process for collaborating?

A: Currently we are in a bar; this is admittedly an important element of our work.

M: I wouldn’t consider myself a possessive girlfriend, however, I “collaborate with”/contact Anna… how many times a day?

A: …Twenty or thirty, depending on what we have going on, considerably more often then my boyfriend. I think where you really see this in our work is with the lack of formality in relating to one another when performing, we laugh when things are funny, we openly discuss how to cope with situations that arise; constant communications is part of our relationships and our art practice.

TPT: Do you have individual practices? Can you talk about them?

M: We are currently concentrating on our collaborative practice; neither of us has made solo work in 3-5 years.

TPT: How did the context of the Pozen Center inform your work?

M: We hated the Pozen Center. We were absolutely thrilled to be presenting work at Mass Arts and we were excited to be working in a space of such importance but found the space physically overwhelming.

A: I was terrified of the Pozen Center, as soon as we walked in. I was terrified of the stage and the grandeur. We usually work with actions that can insert themselves into a pre-existing context and the Pozen Center demanded that we make ourselves the center of attention.

M: If we had not been in the Pozen Center we would not have executed this piece this way, the scale of the room forced us to work with height, the insurance restrictions of the College forced us to change the structural formation of the piece and the theatrical lighting forced us to interact with set and audience in a way that we usually avoid. We now love the Pozen Center.

TPT: How did you communicate with one another in this piece?

M: When we are performing we do not take on any characters of personas. When we laugh its real, when we swear it’s real, when we fall its real.

A: When were perform we have fluid conversations, we work thought problems and make jokes, we pretty much discus things exactly the same way we would if we weren’t doing something ridiculous. Anything else would be acting.

TPT: How did you decide on the actions and imagery in this piece?

M: I was on an OK Cupid date, and it was going great. The guy had been a curator or something in St. Louis, which gave me a false sense of security of what I could or could not talk about. Due to nerves I had skipped dinner and we were meeting for drinks … after a few cocktails things were going so well that we moved on to a restaurant. At some point I said “reality television is really important to me”, to which Jude said “You just said ‘reality television is really important to me’ RED FLAG.” I assumed he was making a joke and continued to discus my love of all things high and low culture. I never heard from Jude again, but since then I have had many conversations of how I define Red Flags, as well discussions about all of the attributes that make me a red flag.

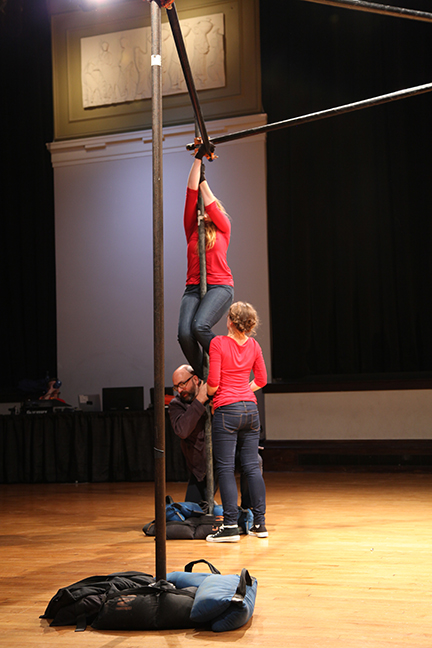

A: Meredith is one of the funniest people I have ever met and she tells this story really well, more importantly I have made her tell this story to so many people who are much more important than us, so for me the image of the red flag has shifted from a portrait of Meredith to a portrait of our ridiculous relationship. When we arrived at the Pozen center we found these poles that were used to hang lights, they were reminiscent of flag poles and I immediately climbed to the top of them. They were wonderful objects and it became pretty obvious that we needed to raise ourselves as red flags on them. We wanted to present a third pole in the piece, a place holder for the audience to physically or intellectually position themselves in and consider how they could stand beside us. The joined triangular structure was the result of us worrying the College, they wouldn’t let us do the piece without the brace which turned out to be a win/lose situation, we lost the direct reference to a flag pole but it the end it strengthened the sculptural footprint of the piece when we were not performing.

M: I also got that one guy to take off this shirt while he was building it.

TPT: Do you often use endurance actions in your work?

A: Often, it’s hard to end performance art and if a work doesn’t have a built in ending it’s the only decision that makes since, beyond that it connects directly to our life styles – we both work multiple jobs, run Happy Collaborationists and still try to make art. Our existence is a practice of endurance and we don’t quit anything until our bodies or minds give out.

M: Our practice is also based on a concept or idea of generosity. What can we give the audience? What can we give each other? It only makes sense to do any of these things for as long as humanly possible.

TPT: Can you talk about the color red?

M: Red is a big color; it’s bold and demands attentions.

A: I don’t think we started working with red for the sake of aesthetics, rather we were interested in several objects in our culture that others had decided to make red: the red carpet, the red flag and the red solo cup. We selected aspects of everyday existence that we were interested in and they all happened to red, because of that I think we have started to really consider this color aesthetically. It took us about five hour of shopping to find the “right” red shirts for this piece

TPT: Can you talk about the intention behind the actions? Did that intention change once your were in the piece?

M: Our intent with this piece was to fail. It was important to insert ourselves symbolically as a flag, but it was equally important to carry out an action that would ultimately become physically impossible. Our intention did not change because we successfully failed.

A: I believe that the in-time transformation of the piece happened in its second occurrence. When Meredith and I started, we were both already physically exhausted. After I helped her to the top of the pole, I could not quite reach the top myself. After we had both fallen, it because obvious that we could not continue to simultaneous execute this sculpture – so we decided to reformat the action and she began to lift me the top over and over again, until I was no longer physically able to grip the bar that was holding me up. She was still standing by me, but we had to combine our strengths to keep the sculpture alive.

TPT: What is Happy Collaborationists?

M: Happy Collaborationists is our collaborative curatorial practice, we use it to support other artists working in performance, installation and media arts.

TPT: What are the blue wigs all about?

A: Everyone always asks about Happy C’s wigs, and that’s the point. They are goofy and approachable, we work with conceptual art, sculptural performance and a lot of other forms of artwork that make people uncomfortable about asking questions and engaging with us. The blue wigs started as a wacky stunt that had a lot to do with the fact the we all looked good in blue wigs, but they remained because over and over again someone who wants to ask a question about the artwork can’t do so until they are already having a conversation with us, and no one has ever been awkward about walking up and asking about the wigs, or asking to get their picture taken with us. It’s not a performance it’s more of a scheme.

TPT: What were some of your expectations/ hopes (if any) of your audience?

M: That they don’t feel trapped. I want our audience to make their own incredibly conscious decisions as to what the piece means to them, and how they chose or choose not to interact with a work. Ultimately I am a looking for acceptance.

A: I hope that an audience engages and interprets our actions from their own perspective, once you make a work it become autonomous and I believe that any individuals perspective on a piece that I do is equally valued to my own.

TPT: Were there any moments that surprised you?

A: Yes and no, we never know how our interaction will unfold in a work, so we never know exactly what to expect. When you don’t have precise expectations, it’s hard to be surprised.

TPT: How was performing in Boston different from making work in Chicago?

M: We couldn’t find a liquor store anywhere.

TPT: What imprints did Boston leave on you?

M: This was our first time engaging in an artist exchange and we are grateful for the friendships we have made and are inspired by the work of these Boston based artists. We are blown away by the generosity of the individuals we have met.

TPT: Can you talk about the duration of this work?

M: We waited until a crowd gathered and then reacted to our physical limitations.

A: We performed the work once and were exhausted. After a recovery period we felt as though we could continue the action, so we re-executed the piece. We performed until I could no longer grip the pole and we had to stop.

TPT: What is inspiring you at the moment?

M: The ability to laugh at ourselves and knowing when to laugh at each other. We make work about things we can confidently answer about one another lives and actions.

TPT: Any words of wisdom?

M: A Snickers in not a meal…

A: except when it is.

Red Flag, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Red Flag, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Red Flag, 2012 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Adam Rose

Adam Rose is the Artistic Director of Antibody Corporation, a non-profit organization specializing in mind-body and occult research. Since its founding in 2009, Antibody has presented research findings in a variety of media including performance, video, and text.

For Rough Trade II, Adam Rose created, Neu Iconoclasts: Wig Party, 2012. The following is an interview between Adam and The Present Tense.

TPT: Your work explores the interstices of dance and performance art. Do you feel that this has made your work more or less accessible to certain audiences?

AR: Dance and Performance Art audiences tend to have different expectations, and I encounter different obstacles in each context. Where as a dance audience might question my technique or level of training, or be confused and put off by the imagery I employ, a performance art audience might be disappointed by seeing something that’s ‘just a dance.’

I think dance and performance art are two contemporary manifestations of a more primordial performance tradition that underlies them both. I learn from performing in both contexts, and any confusion or misunderstandings that might arise are ultimately productive.

TPT: Do you have an ideal context that you like to make work in?

AR: No, no context is ideal–not dance, not performance art, not butoh. They each have their unique obstacles and expectations. I enjoy the chance to perform in every context.

TPT: Can you talk about the role of personae in your work?

AR: I don’t believe in the idea of a single self or single self-identity. Anyway, I think it would be boring to perform as just me. So I try to push self-expression to the point where the different aspects split off into separate characters with their own lives. ”My name is Legion, for we are many,” (Mark 5:9). But basically I have two personas, a male persona and a female persona, Elena.

TPT: Who is Elena?