Reflecting Torpor, an essay published in peer reviewed journal, PUBLIC Journal: Art Culture Ideas Issue No. 58: Smoke: Figures, Genres, Forms, 2019

SANDRINE SCHAEFER | REFLECTING TORPOR 2019

Sandrine Schaefer, Torpor (Pace Investigations No. 5) Time Map (2017). Mixed media drawing. 28 x 35.5 cm. Courtesy of artist.

Torpor (Pace Investigations No.5) was a performance artwork I developed on site at Banff Centre for Art and Creativity during the Banff Research in Culture program, themed The Year 2067. Sited on a pathway on the Banff campus, Torpor unfolded during dawn and dusk on the same day. The actions and materials of the performance were site-specific. During sunrise and again at sunset the performance repeated eight times consecutively, its duration either increasing or decreasing. This increase or decrease in duration mimicked the shifts in average heart and breath rate bears experience as they enter and exit torpor. As this constriction and expansion of time occurred, the performance was forced to shift. Some actions that made up the performance sped up. Some slowed down. Others merged to become different actions all together. Some actions were abandoned, while others gained significance. Regardless of how the performance adapted, the tensions between acceleration and deceleration, as well as between mechanical, geological and felt time, were palpable.

Torpor occurred on 9 August 2017 from 3:49am-6:20am and 9:14pm-11:43pm MT and was witnessed through various fragmented means: in the flesh, through a webcam located on the Banff Centre campus, through image-based documentation, video documentation captured through a body cam I wore during the performance and a surveillance camera hidden inside a decoy rock, and now through the following reflective text.

Torpor is a performance art piece that contains multiple performances. The performance is composed of 13 individual actions. Similar to what happens when the performance repeats at changing durations, some individual actions are described through this text, some are merged, and many are left out. Leaving actions out is not an assignment of insignificance. The choice of leaving in and leaving out is a problem of translation. The essence of some actions can be translated into the written word. For others, this is impossible. It is also important to acknowledge that this text participates in the contradiction of documenting performance art. In the final chapter of her seminal text, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, Peggy Phelan articulates that a distinguishing feature of performance art is its privileging of the present moment and argues that any attempt to save, record, or document a performance is something other than performance and risks betraying its own ontology.1

This reflective text does not attempt to save, record, document or reproduce Torpor. This is impossible. This text attempts to understand something about the work through the act of writing. What I choose to leave in are actions and ideas I wanted to investigate through strategies of embodiment at the time I made Torpor and now wish to engage further through remembering. The following segments are ideas generated by reflecting on the actions and execution of the performance.

The Landscape is Always in Relation

My work offers opportunities to gather and proposes ways to share time not accessible elsewhere in life. Using a site-sensitive approach, my work tends towards material sparseness to draw attention to what is readily available in a location. When I say site-sensitive, I mean that all phases of the work (the seed of an idea, research, execution, archiving, etc.) acknowledge and adapt to multiple past and present identities a place holds while exercising foresight into what a place may become in the future. This approach seeks to dismantle traditional modes of viewership by de-privileging sight as the primary sense with which to engage the work and celebrates liveness through its adaptation. This liveness is, of course, slippery. In his book, Felt Time, Marc Wittmann articulates that the temporality of the present lasts up to a maximum of three seconds.2 After three seconds, any feeling of presence or “nowness” is assisted by short-term memory. Following Wittmann’s claim, in my work’s attempts to celebrate, liveness, it is also celebrating the impossibility of “the now”. It acknowledges that the past is always constructing the present, and any notion of the future is nothing more than a fabrication of present thought.

In all phases of the work, I am asking:

Do I need to do this?

Do I need to do this here?

Do I need to do this now?

Must it happen this way

The Body

We all navigate the world through the vehicle of a body. The body is the most readily available material. Therefore, it is an accessible material. It is a familiar material. It is a sensational material. It is a political material. It is a transmissive material. It is a receptive material. It is a conductive material. It is a collective material. It is an exclusive material. It is an inclusive material. It is a decaying material. It is ecologically responsible material. It is an economic material. It is an indulgent material. It is an obvious material. It is a redundant material. It is a reliably unreliable material. It is a confrontational material. It is a spectacular material. It is a banal material. It is a material that interrupts. It is an abundant material. Is a forgotten material. It is an articulate material. It is an inarticulate material. It is a volatile material. It is a fugitive material. It is a demanding material. It is a fragile material. It is a durable material. It is an insistent material. It is a burdened material. It is an urgent material.

Sandrine Schaefer, Bear Breath (2018). Action from Torpor (Pace Investigations No. 5) re-performed for camera. Photograph by Daniel S. DeLuca. Courtesy of artist

An outdoor pathway in view of a webcam emerges as the site that generates the most complexity for Torpor. In this place, my body is reminded that it is a visitor. My skin cracks and nose bleeds from the lack of moisture in the air. The heightened elevation causes occasional dizziness and strains my breath. Developed on site during a record-breaking season of wildfires in British Colombia, Torpor was made in and through smoke. Ash and smoke linger in the air, making it even harder to breathe. As a person living with asthma, I am advised to stay indoors. Breath begins to lead the work.

Sandrine Schaefer, Becoming Bear Action Map (2017). Mixed media print. 23 x 30.5 cm. Courtesy of artist.

Snore

In the torpor state, the average bear heart slows to eight to ten beats per minute (compared to 40 beats per minute during regular sleep.)3 In comparison, the average human’s resting heart beat averages between 60-100 beats per minute.4 The average bear takes one breath per minute when in torpor. I wanted to understand the circadian rhythms of a non-human being and feel what this slowing down would do to my body. I knew that this is an impossible task. I know humans cannot enter torpor.5 I recognize that I am at a particular disadvantage because my heart rate rests higher due to my asthma. Knowing did not squelch my desire to become bear.

I began training myself through various Pranayamic breathing techniques. The goal was to slow my breath to one breath every 45 seconds for five minutes. To put into perspective, anything under twelve breaths per minute is considered “abnormal” for a human adult.6 I was able to train myself to comfortably take one breath once every 37 seconds for five minutes. Although closer than I had ever been, I was failing to become bear. I created another action to produce the rhythm I was after. I pull my foot out of my boot where a small speaker is hidden. The speaker amplifies the sound of a black bear’s snore while in torpor. This is a reward for the curious. The sound is soft, an invitation to come close. It is an invitation to break any assumed etiquette witnesses may be assigning to this encounter learned from other experiences with performance.

Swell

As I breathe the smoke from nearby wildfires, my airways swell. At dawn, the light swells. The duration of the performance at dusk swells. The swell of sound punctuates an otherwise quiet place and extends the reach of my singular body.

Jodi Dean opens Crowds and Party by describing an experience during an Occupy Movement’s general assembly at Washington Square Park where the People’s Mic was used as a form of amplifying the voice of one by putting it into the bodies of many. Dean describes how the threads of collectivity were severed when a speaker ended a speech with “everyone is an autonomous individual.” Dean argues that this recurring “collective strength dissolved into the problem of individualism” was the demise of the Occupy Movement.7 I wonder if the tool of the People’s Mic can be used as a strategy to generate collective strength in the site of this performance. I travel to one end of the path, stand behind a patch of trees and call out:

“Mic Check”

If someone answers back,

“Mic Check”

I continue,

“Swarms take the form of a collective body”

“Swarms take the form of a collective body”

“engaging a task”

“engaging a task”

“that a singular body cannot.”

“that a singular body cannot.”

“Swarms are related to influence and intuition.”

“Swarms are related to influence and intuition.”

“Swarms may erupt in social situations”

“Swarms may erupt in social situations”

“as encounters with spectacle”

“as encounters with spectacle”

“Swarms may erupt in social situations out of a desire”

“Swarms may erupt in social situations out of a desire”

“to acquire an object”

“to acquire an object”

“or have an experience.”

“or have an experience.”

“Swarms may erupt in social situations out of desire to assist.”

“Swarms may erupt in social situations out of desire to assist.”

“A swarm is a temporary gathering.”

“A swarm is a temporary gathering.”

“To understand the desire to swarm,

“To understand the desire to swarm,

“one must acknowledge the desire to fragment.”

“one must acknowledge the desire to fragment.”

“Dissemination occurs after”

“Dissemination occurs after”

“the subsequent dispersal of a swarm.”

“the subsequent dispersal of a swarm.”

“The singular parts”

“The singular parts”

“that once made up the swarm”

“that once made up the swarm”

“are released.”

“are released.”

“Changed in some way by the experience,”

“Changed in some way by the experience,”

“these parts spread”

“these parts spread”

“the auric artifact/leftover charge”

“the auric artifact/leftover charge”

“that once surrounded the swarm.”

“that once surrounded the swarm.”

During dawn, this amplified transmission fails. No one reciprocates my call into the early morning darkness.

Shrink

“The more people travel upon a path, the clearer the path becomes. Note here how collectivity can become a direction: a clearing of the way as the way of many.”

- Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life 8

At dusk, the light shrinks. The duration of the performance at dawn shrinks. The actions shrink. We all become small through the view of the webcam. I sweep the path with a large broom. I kick up dust that mingles with the smoke from burning forests. I then hold the broom over my head and sweep the sky. This is an action that is made specifically for those watching the live surveillance feed. The broom, covered with reflective paint, catches light to give the illusion that my form is larger.

This action of sweeping the sky is simultaneously sincere and absurd. It knows it is a joke. It knows it is an inside joke. In 2006, artists Milan Kohout and Milan Klic attached a broom and a bag to two 10 metre rods, hoisted them into the air on Boston’s City Hall Plaza in an attempt to “clean the sky” in a performance titled Cleaning the Sky.9 This action is simultaneously sincere and absurd. Sweeping, a human convention to clean up the remnants of daily life on human scale somehow feels appropriate yet cannot escape its inadequacy.

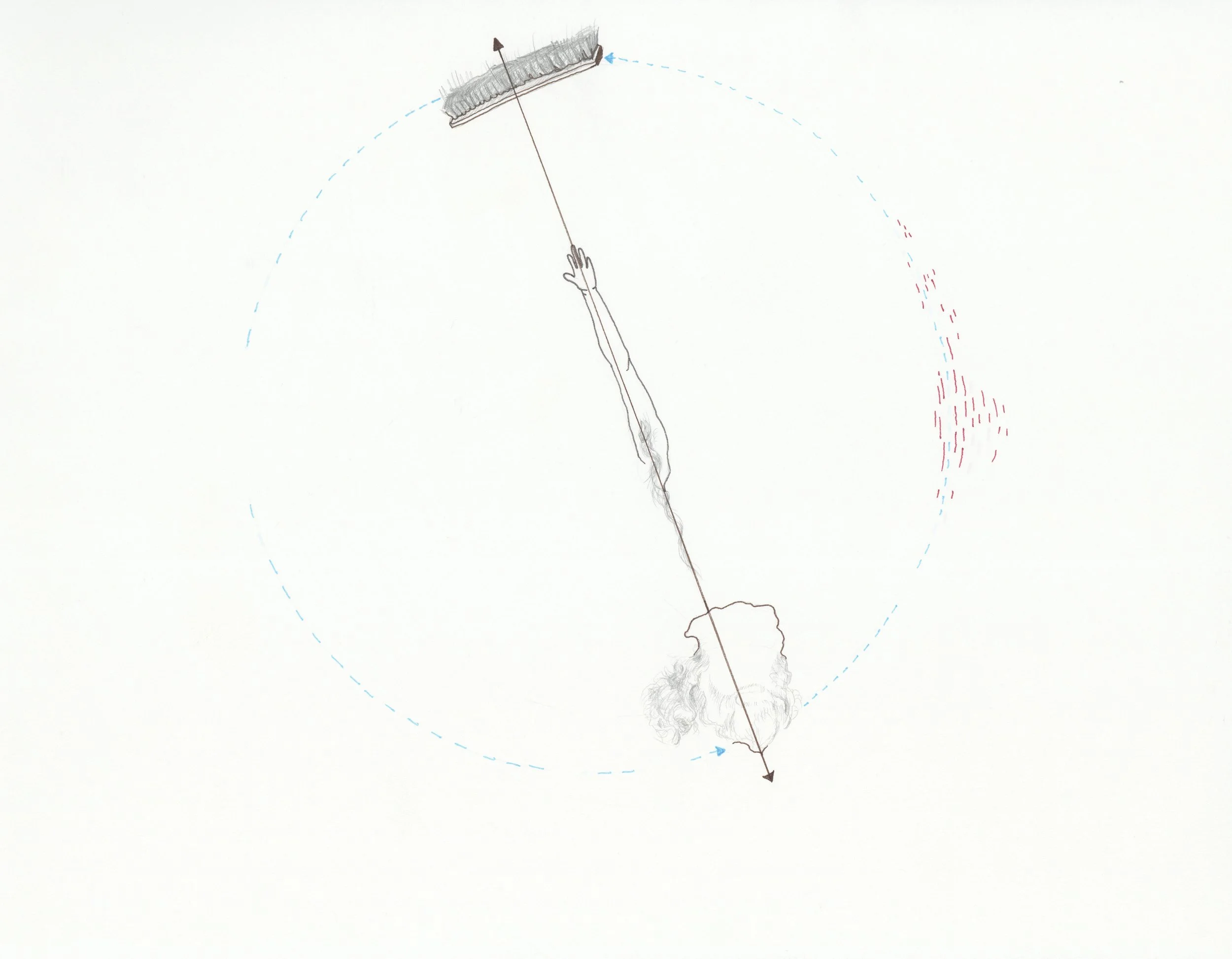

Sandrine Schaefer, Sweeping the Sky Action Map (2017). Mixed media drawing. 28 x 35.5 cm. Courtesy of artist.

In Visibility

Artist Alastair MacLennan uses the example of phases of water when talking about preserving the integrity of an action while adjusting to varied performance conditions. Water is always water whether it takes the form of moving water, ice or steam. What shifts through state change is not the essence of water, but how the water is made visible and the pace at which the water moves.10 I am reminded of MacLennan’s words as I prepare for Torpor. I notice how my pace changes in response to the impact of the smoke on my body. I observe how the smoke changes the visibility of the mountains in the site I have chosen for the work. These tensions between visibility and invisibility guide the work. Making a performance during twilight hours only, keeping the performance in motion along a path (which destabilizes a clear performance area), and offering a live surveillance feed as a mechanism for viewing created multiple scales of visibility through which the piece was accessed. These choices reveal the impossibility of a coherent witnessing experience. The presence of the webcam that captured a mobile performance also creates a condition that calls the performing body into question. Who is on display? Me? You? The elk grazing next to the path at sunrise? All of us? None of us?

An abundant buffaloberry season and wildfires in the summer of 2017 resulted in an increase in bear activity in “human” spaces in Banff. The activities of bears and other wildlife are closely monitored in Canada through live feeds captured by cameras hidden throughout the wilderness. This footage is watched by Wildlife Monitors and sometimes posted online to educate tourists about wildlife in the area. The webcam on the Banff campus functions similarly. It was installed to stream the construction of the Shaw Amphitheatre and has remained to capture human activity and promote tourism to the Centre.11 These surveillance cameras are carefully placed so that they cannot be seen and, in the wilderness, these cameras are actively camouflaged. Cameras are strapped to trees in waterproof boxes that resemble tree bark. In wildlife film and television, there is a budding genre of shows and films presenting footage collected by cameras hidden inside environmental decoys. These decoys include rocks, food sources (in the case of bears, beehives and fish that swim), a robot mirrored on all sides to reflect the surroundings,12 and animatronic animal decoys that imitate the animal under surveillance.13 Much of this footage is edited to anthropomorphize animal behavior in an attempt to induce empathy.14 What happens if we turn these strategies for observing non-human life on ourselves? How might curiosity shift? What kind of stories will form? During a time when tools of human surveillance are also being repurposed and put into the hands of many (Bodycams putatively monitor police violence [while also rationalizing and expanding it], vigilance through the ubiquity of camera phones, etc.) can these tools be used within the site of an artwork to propose a different kind of power and gaze?

Sandrine Schaefer, Torpor (Pace Investigations No. 5) (2017). Video footage captured from hidden camera. Courtesy of artist.

TRAnsferenCE

“Playing games of string figures is about giving and receiving patterns, dropping threads and failing but sometimes finding something that works, something consequential and maybe even beautiful, that wasn’t there before, of relaying connections that matter, of telling stories in hand upon hand, digit upon digit, attachment site upon attachment site, to craft conditions for finite flourishing on terra, on earth.”

- Donna Haraway, Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene15

Torpor moved through astronomical, nautical, and civil twilight, meaning the majority of the piece unfolded in the dark. Witnesses, who experienced the work in the flesh, were offered small flashlights to illuminate areas and actions of interest in the dark. Shining light in this way is a form of pointing. Pointing isolates and locates one in space and time and simultaneously builds relationships between things. Giving the audience the choice to shine light on the performance also invited what I describe as the gray zone of performance: the encounter of equality between the artist (and, in this case, also the body on display) and witnesses. This moves beyond participation and interaction. In the gray zone of performance, the witness is aware of their implication in the fulfillment of the work. While reciprocity is often the artist’s ideal, one may bear witness against their will (as is often the case in other situations that produce witnesses). This may result in one rejecting the encounter, responding when unsolicited, or perhaps even reacting with hostility. A witness may take unexpected liberties while navigating a piece of performance art as they become more comfortable, experience boredom, frustration, or confusion, and confront their feelings around how the performance is spending shared time. This charged territory between artist and witness is performance art’s primary concern. The gray zone of performance is fertile ground for artist to witness TRAnsferenCE. In artist-to-witness TRAnsferenCE, bodies communicate beyond obvious tendencies; reciprocal exchange builds shared lived experiences that extend the performance beyond the moment of its occurrence; the performing body is called into question; and, most importantly, the work’s inquiry is transferred into the bodies of those witnessing. In other words, in artist-to-witness TRAnsferenCE, another temporality emerges. In this temporality, the TRACE which endures beyond the immediate life of the performance remains, now archived with/in the body of witnesses. Like smoke, the lingering TRACE that has been transmitted into the bodies of those who have shared in an experience can be corporeally felt long after the performance has concluded. TRAnsferenCE always leaves residue which simultaneously pulls the present toward the past and the future.

Inspired by Donna Haraway’s writing on string figures, I attempted to play a one-to-one string game during Torpor. I stretched a clear string between my fingers and presented it to one of the witnesses. In the darkest hours of the performance, I held a flashlight in my mouth that illuminated the otherwise invisible string. Without speaking, I waited until the person approached and played. If they did not, we would observe the figure between my hands. I chose to play the Hand Cut/ Hand Trap game that moves through a position where the string wraps around the wrist of one player and ends with the player’s hand being set free. This string game begins with the same position of the popular Cat’s Cradle. Most who recognized the figure and chose to interact tried to play Cat’s Cradle. There were moments of surprise when the game did not unfold as expected. In one interaction, I was taught a string game I didn’t know or recognize. In this moment, it was clear that the gray zone had been achieved.

The string game was activated once during sunrise and several times during sunset. Similar to the people’s mic action, the invitation to play was mostly unreciprocated during Torpor. Interactive actions, particularly ambiguous ones, are subject to being trapped in this state of waiting. This action presented a series of challenging conditions. While there was not a clearly designated “performance space” in this work, people tried to create one by gathering in certain figurations and maintaining a uniform distance between my body and their own. The string game required those willing to play to cross this boundary and place their own knowledge and performativity on display. I did not speak unless someone spoke to me. I imagine this created confusion for witnesses, as the negotiation between us relied on nonverbal communication (something often reserved for other kinds of relationships). The action was particularly intimate in that the string caught the witness at the pulse point of the wrist. Was this touch intended to confine? Was it meant to be a gentle embrace? Can both of these exist at the same time? While reciprocity was the ideal, ambiguous conditions can produce ambiguous results. I spin my web and wait to catch something. I wait to give. I wait to receive. I wait for a pattern to emerge. As I wait, I am reminded of the limits of my individuality.

Sandrine Schaefer, String Game Action Map (2017). Mixed media drawing. 28 x 35.5 cm. Courtesy of artist.

Torpor attempted to momentarily strip the notion of time from its putative anthropocentrism. It is a work that reminds us that humans are small, engulfed by the cycles of the earth’s regeneration, engulfed by the complexity of contemporary surveillance practices that we have created for ourselves and other non-human beings. Torpor asks how bodies call and respond, and how these transmissions can lead us to think through our collectivity beyond simply sharing time in the same place. Simultaneously, the work asks us to consider curiosity as a strategy, redefining its perceived boundaries through a practice of play.

NOTES

1 Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge,1993).

2 Marc Wittmann, Felt Time: The Psychology of How We Perceive Time. Translated by Erik Butler. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016) 50.

3 Michael Fitz, “Bear Hibernation,” National Park Service, November 21, 2013, https://www.nps.gov/katm/blogs/bear-hibernation.htm.

4 “Target Heart Rates,” American Heart Association Website, https://healthyforgood.heart.org/move-more/articles/target-heart-rates (accessed 29 May 2018).

5 I discovered that I was not alone in this desire. In 2014, NASA announced that, in an effort to cut the cost of a human expedition to Mars, they were researching how to put a human crew in torpor. Reducing the astronauts' metabolic functions would minimize life support requirements and make missions less costly.

Irene Klotz, “NASA Eyes Crew Deep Sleep Option for Mars Mission,” Space.com, October 14, 2014, https://www.space.com/27348-nasa-mars-crew-deep-sleep.html

6 “Heart and Breathing Rate,” Sleep Renewal, https://www.sleeprenewal.co.za/heart-and-breathing-rate (accessed on 29 May 2018).

7 Jodi Dean, Crowds and Party (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2016), 21-22.

8 Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 46.

9 Witnessed first-hand in 2006, Clean the Sky was part of Mobius Inc.’s project titled In Between. The project involved Mobius Artist Group and invited collaborators to make live artworks sited on Boston’s City Hall Plaza.

10 Alastair MacLennan, interview with author, 11 May 2018.

11 The Banff Centre webcam and other webcams can be accessed on Banff and Lake Louise Alive, https://www.banfflakelouise.com/trip-planning/webcams (accessed 29 May 2018).

12 Bears: Spy in the Woods, directed by John Downer (2004; United Kingdom: John Downer Productions Ltd.), Television documentary.

13 Spy in the Wild, directed and produced by John Downer, aired 2017-, BBC.

14 An example can be found in Episode 1 of the television series Spy in the Wild (12 January 2017, BBC) when a group of Langur monkeys are depicted as demonstrating “emotions that have rarely been observed.” When the small animatronic monkey sent to surveil the monkeys falls to the ground, the monkeys are depicted as mistaking the “lifeless” robot for a “baby.” Here, the monkeys are portrayed as grieving the death of one of their own. John Downer, dir., Spy in the Wild, Season 1, episode 1 "Love," aired 12 January 2017, BBC.

15 Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 10.