Leap Before You Look- A New Happening (2015)

In 2015, I was the Teaching Artist in Residence at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston in conjunction with the exhibition, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957. Over 3 months, I led a multi-session workshop with the Teen Arts Council inspired by the exhibition. Black Mountain College was not solely an art college, but a school that placed art at the nucleus of learning, rather than at the periphery. Founder of the college, John Rice aimed to foster an environment where constant questioning was expected and teachers took on the role of a discussion leader rather than the possessor of all answers. This led to many collaborations between students and teachers. Rice named this “group intelligence” and insisted that it was a necessary vehicle for social change. In this workshop, it was critical that our activities reflected the value of “group intelligence.” During our 3-months together, the ICA’s Teen Arts Council collaborated with one another, myself, and artists Robert Chamberlain and Philip Fryer to try on, reimagine and challenge many of the methodologies practiced at Black Mountain. Our efforts culminated into the creation and public performance of an original Happening that reflected our present-day collective concerns.

I am a multidisciplinary artist. My artwork often takes the form of durational performance art and installation. My work is always site-specific. It requires time and prolonged attention. It is ephemeral. Often times, my work operates at the edges and in-between spaces. It asks viewers to move around. To be curious. My work is not easily categorized. It often incites confusion. The legacy of Black Mountain College has been part of my personal artistic lineage since I was a young art student in the 90’s. Black Mountain was frequently referenced by my teachers and peers and the more I learned about it, the more it helped me to embrace my experimental tendencies in art making. The methods practiced at the college also gave me permission to challenge how I approached my own learning and has continued to influence how I now, inhabit the role of “art teacher”.

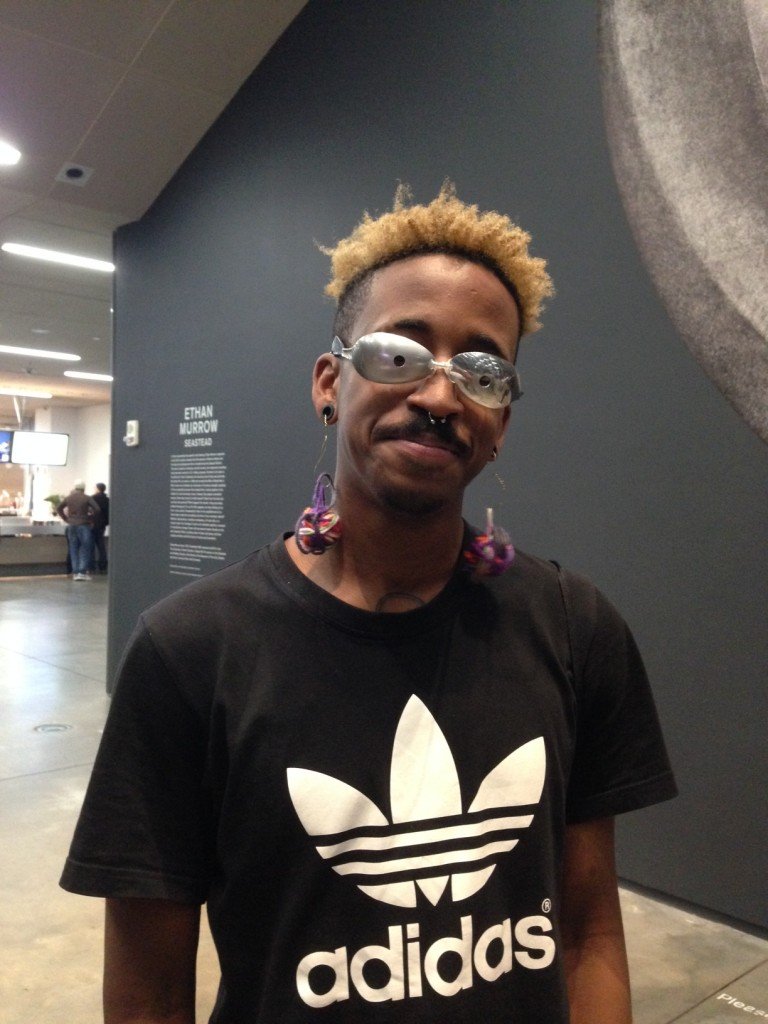

Black Mountain’s non-hierarchical methods included cooperative labor. Students participated in farming, construction projects, and kitchen duty as part of their “holistic” education. These activities blurred boundaries between “art” and every-day encounters. The college epitomized the notion that art can be found everywhere and in anything, through what faculty member Anni Albers called “Shaping out of the Shapeless” even the most mundane objects and materials could be transformed into art. Students were often challenged to work with “basic” materials (defined as paper, metal, and wire) while avoiding tools traditionally associated with these materials. Looking at the Leaf Studies of Josef Albers, and the works of Ruth Asawa in addition to Anni Albers and Alexander Reed’s jewelry made from every-day objects, we used what we identified as basic materials and everyday objects to create costumes for our upcoming Happening. Through this process we questioned what “everyday materials and objects” looked like in 2015 vs. the 1930’s-50’s.

Perhaps part of Black Mountain’s emphasis on experimenting with basic/everyday materials was a result of the college’s limited resources. Another example of resourcefulness practiced at Black Mountain was how faculty taught new works that were not yet available in reproductions. Art critic Clement Greenberg, would often speak about works in his seminars without slides. This is hard to imagine now, in a time where cameras and digital images are ubiquitous!

To better understand this condition, we dispersed throughout the Leap before you Look exhibition and spent an uninterrupted 30 minutes observing a single piece that we gravitated towards. When the group reconvened, we described the pieces we chose to one another only using words, gestures, and/or actions. The rest of the group would then guess which piece each participant had chosen. This was a notable exercise because we mostly guessed correctly! This proved that we had successfully developed a group intelligence, a nuanced way of communicating with one another that was no longer reliant on speech.

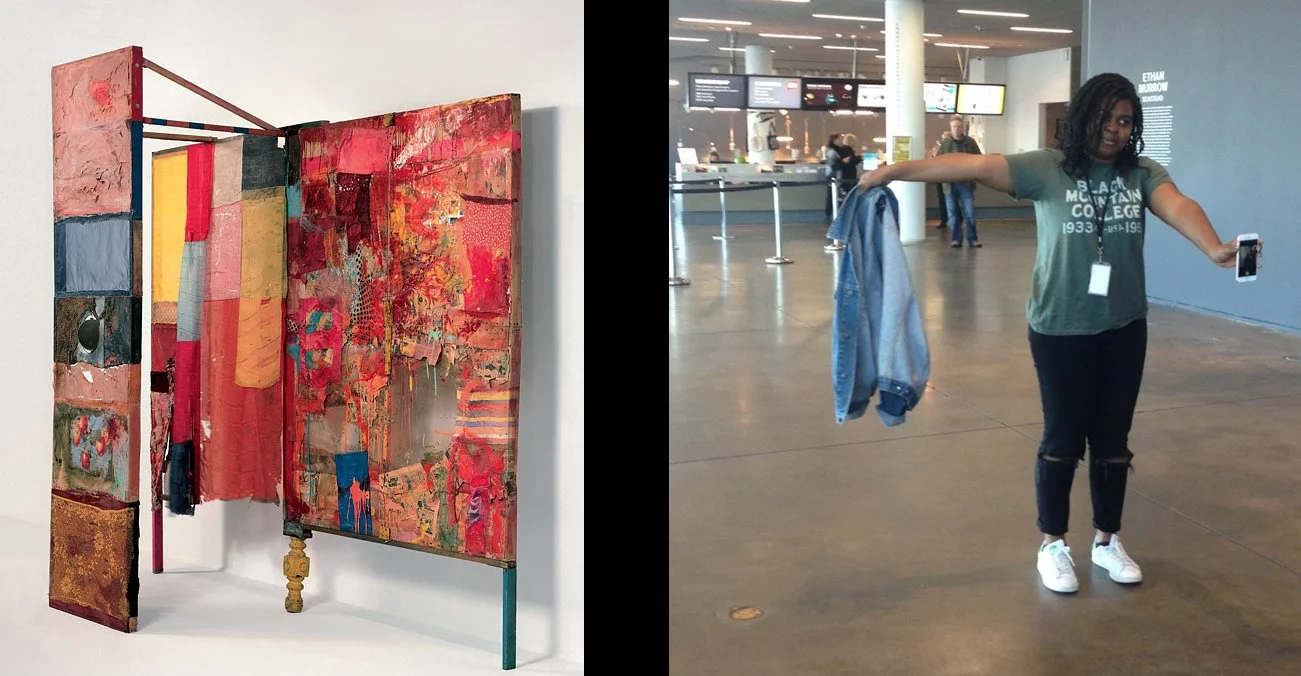

Sienna Kwami’s gestural description of Robert Rauschenberg’s Minutiae (1954)

We then interpreted the methods John Cage used to create Theatre Piece No. 1 to develop a structure for our own Happening. Similar to Theatre Piece No. 1’s we used simultaneity and chance as guiding principles. We used Cage’s method, “chance operations” and the literary explorations of Charles Olson (mainly Projective Verse) to build textual elements for our Happening (instructions, scores, and poems).

So what actually happened at our Happening?

It was performed for 45 minutes and included a tap-out structure. Our rule was that only 5 performers could activate the performance space at one time. Anyone in the group could enter the Happening when they felt that it needed to change. The actions that made up the Happening took the form of 65 instructions collectively generated by the group. Before a performer entered the performance space, they took an instruction from a box at random. The instructions were performed simultaneously until exhaustion or until the performer was tapped out. Some of these instructions included

LISTEN TO YOUR HEARBEAT

SIT NEXT TO 3 DIFFERENT AUDIENCE MEMBERS. ASK THEM WHAT THEY THINK OF THE HAPPENING. SHOUT OUT WHATEVER THEY SAY.

WRITE YOUR FAVORITE WORD ON A PIECE OF PAPER. SLIP IT INTO SOMEONE’S POCKET WITHOUT THEM NOTICING.

MAKE A PILE OF THINGS THAT ARE ALL THE SAME COLOR

TELEPHONE A RANDOM NUMBER AND ASK FOR THE NAME OF THE PERSON WHO ANSWERS. TELEPHONE A KNOWN NUMBER AND ASK FOR THE NAME OBTAINED FROM THE FIRST CALL.

Our Happening was performed for the public and was followed by a micro-workshop lead by the Teens where the strategies we used to design and execute our piece were shared. This sharing felt important to fully translate the notion of “group Intelligence”. A quote that feels important to share here comes from John Rice, “The individual, to be complete, must be aware of their relation to others. Here the whole community becomes their teacher.”