The following is text written by Sandrine Schaefer that archives Near Death Performance Art Experience, 2013, Boston, MA. Originally published on ThePresentTense.org

This Generation’s Population of Ghosts: Near Death Performance Art Experience

Text by Sandrine Schaefer

As performance art moves into a phase where it faces the same commodification, professionalization, and institutionalism that other art mediums have endured, artists and organizers are challenged with how to maintain the authenticity of the medium’s lineage. Within this medium, where artists call upon their physical, mental, emotional, and intellectual endurance to challenge the parameters of real time, it is impossible to remove mortality from performance-based work. As artists connected by this medium watch one another’s practices evolve and mature, they are simultaneously watching each other age. They witness their bodies change, ideas develop, and they can see their impact on each-other and the future generations of performance artists with whom they are connected.

Working with ideas around the cycles of life and death, Vela Phelan conceived of Near Death Performance Art Experience (NDPAE), a performance art event that offered an opportunity for multiple generations of artists to create live works around this theme. In a simple stroke of irony, NDPAE had its own experience with death. Originally scheduled to unfold over 2 days at Fourth Wall Project in Boston and after months of planning, Fourth Wall was temporarily shut down due to permitting issues, a historic plague among Boston alternative art spaces. NDPAE was postponed until further notice. The event fortunately found its afterlife within the walls of the Boston Center for the Art’s Cyclorama, a stunning space with a history of being used as a war memorial. NDPAE was rescheduled for April 21, 2013, coincidentally the birthday of the late artist, Bob Raymond to whom the event was dedicated, and less than 1 week after the Boston Marathon Bombings. For 7 hours, audiences were given time and space to contemplate how we make sense of mortality through the lens of action-based art.

Marilyn Arsem Edge, 2013 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

MARILYN ARSEM Edge

The work began at 3:55pm when Marilyn Arsem sat down at a square wooden table in the center of the Cyclorama. 2 glasses of water, filled almost to the brim, were placed side by side at one end of the table. The natural light that streamed in through the Cyclorama’s dome silhouetted her form. A spectator excitedly whispered that she was holding the room in the glasses. Taking a closer look, I saw that she was, indeed, the keeper of the room, as passersby’s reflections danced across the water. Upon closer inspection, I noticed small bubbles lining the insides of the glasses. A reminder that the water itself had already stood still for a period of time, also a foreshadowing of Marilyn’s prolonged presence within NDPAE. The beginning moments of Marilyn’s piece, titled Edge, unfolded in its ideal context. The Cyclorama was almost silent except for the sound of a clock ticking, emanating from Marilyn. I was grateful for these beginning moments with her as the materials present in the other artists’ installations set around the room suggested that chaos would soon ensue. I meditated on the methodical opening and closing of her eyes. She looked spent, but her presence filled the entire space with a level of intensity and focus that would serve as the foundation for the entire event.

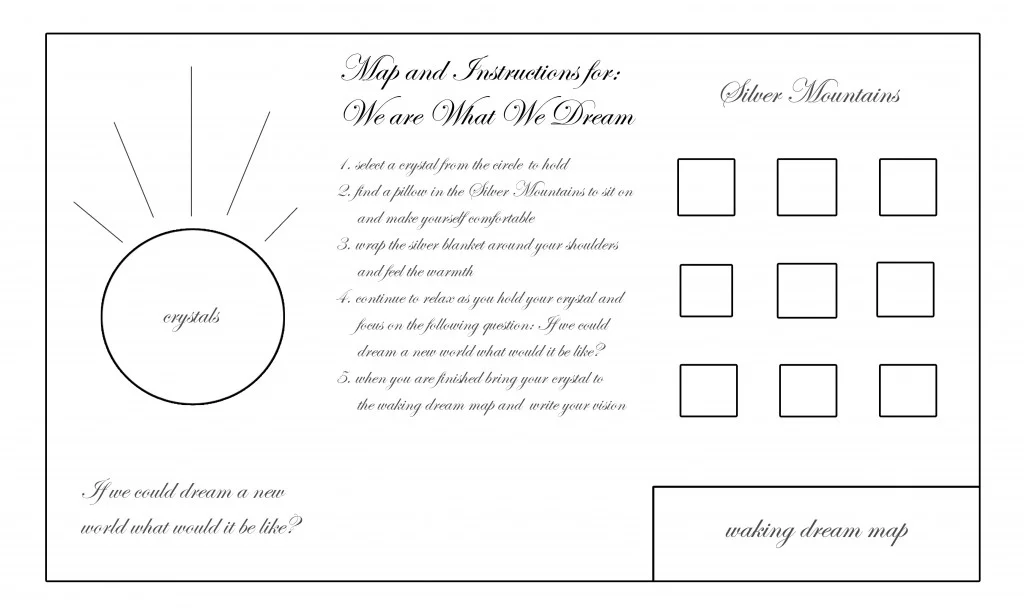

Faith Johnson We Are What We Dream, 2013 photos by Daniel S. DeLuca

FAITH JOHNSON We Are What We Dream

Tucked away in a corner of the Cyclorama, The question, “If we could dream a new world, what would it be like?” was subtly scrawled across the threshold of Faith Johnson’s interactive installation, We Are What We Dream. An assistant approached with a map of the installation. On one side of the space, people sat on pillows wrapped in silver heat blankets, reminiscent of images of marathon runners after reaching the finish line. The map invited me to choose a crystal from a carefully arranged circle on the ground. After selecting my crystal, I was instructed to travel to the “Silver Mountains” to choose a place to sit and meditate on the question: “If we could dream a new world what would it be like?” As I wrapped the heat blanket around me, I noticed the color of my skin reflected in the material. It transformed into a second skin and made me think about all of the people who had worn it before and would wear it after I left. I was able to forget that there are people watching, focusing on the warmth provided by my “mountain” and the sounds it produced. The crinkling of the mylar reminded me of the sound of animals rummaging through piles of trash I experienced during my recent travels in India.

Faith Johnson We Are What We Dream, 2013 photo by Phil Fryer

When I climbed out of my “mountain”, a wall displaying a growing “waking dream map” confronted me. Sitters were invited to write their thoughts directly on the wall. Faith nailed their crystal next to what they had written. With delicate silver thread, she integrated each crystal, each thought, into the map. I felt thankful for Faith’s choice to directly engage her audience in this way. It was fulfilling to see my direct influence on the piece. Exercising this control offered a much-needed respite from the intensity of Marilyn’s individual focus. After I made my contribution to the piece, I stood back and watched the sunlight from nearby windows dance across the crystals and the “silver mountains.” Before leaving India, I spent several days in Varanasi, where I observed the Ghats where bodies of the wealthy are cremated in open air. I watched bodies covered in golden blankets (much like the heat blankets used in Faith’s piece) burn a steady stream of smoke as roaming cattle and goats ate fallen marigolds from the garlands that decorated the corpses. Watching participants interact with “We Are What We Dream” was a similar experience. As people emerged from their “silver mountains,” there was an air that they had been transformed, perhaps even transcended their understanding of time and space.

Travis McCoy Fuller 2013 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

TRAVIS MCCOY FULLER

Back in the main space, the glasses on Marilyn’s table appeared to have moved, making clear that she was pushing the glasses across the table at a tedious pace. Using the ticking of Marilyn’s clock as a sonic foundation for his piece, Travis McCoy Fuller was first to activate the outer edge of the circle of the Cyclorama. Travis employed subtle variations to ask for participation in his piece. He asked out loud, gestured, and spoke softly to offer a more intimate encounter. One of the beginning actions in the piece included two volunteers transporting a pile of rocks on a table to small piles on the floor around the space. Simultaneously, Travis pulled a bag of sand with a hole in it around and through the audience, an arbitrary line of sand marking his path. This was the first in a series of actions that broke the traditional performance space, clarifying that this piece required the audience to witness actively. Travis asked the audience if there was anyone who would like to sit at the table. A man agreed and jumped on top of the table. Travis adjusted his semantics and asked if anyone else would like to sit at the chair that was next to the table. A woman sat in the chair. Travis joined them and the three engaged in the act of eating basil plants in silence. Sometimes when I witness delegated tasks in performance, it feels like an attempt to control the audience’s experience or nothing more than a practical choice. As I watched the woman take delight in nibbling the stems of the basil plant, it became apparent that Travis’ choice to solicit help was an invitation for participants to explore their own performativity. He cultivated a community within the piece, giving the audience the choice to directly contribute to its creation, if they wished.

The performance space was broken again when Travis sat with the audience, took a swig of vodka and passed the bottle around the room. This offering was a gesture that again, leveled the playing field between the spectator and spectated. He proceeded to cut his arms and rub curry into the fresh wounds. The bloodletting directly referenced the corporeal self, while establishing empathy between the audience and the artist. This empathy was ignited again when Travis “challenged” several people in the audience to hold ice cubes until they “turned to water.” This immediately induced the same visceral response that I felt watching Travis cut himself. Although I was not holding an ice cube, I could feel my own fingertips growing numb as I watched and waited with the people in the audience who were given ice.

Travis McCoy Fuller 2013 photo by Philip Fryer

Travis seemed to be moving between meditative and aggressive states. I interpret this as another technique for breaking the performance space. There was time for quiet contemplation (eating plants, balancing stones, watching sand fall) but there were also moments that demanded the audience to be alert (pushing stones, hammering, using a staple gun). While these aggressive actions could be misinterpreted as angst, the destruction served a function to the cycle of the piece. After smashing holes in the center of 2 square tables, Travis balanced one table on top of the other. He stapled the neck of a pair of coveralls around the hole in the bottom table. With the help of the audience, he lifted another pair of coveralls filled with sand onto the table on the top. The sand from one body poured into another, a symbol of reincarnation that took on the form of an hourglass.

Travis McCoy Fuller 2013 photo by Philip Fryer

The piece evoked infinite notions of how humans structure, understand, and attempt to control and change time. Melting ice, the image of the reincarnation hourglass, a loop of John Cage’s saying, “But when we don’t measure time…” fused with the ticking of Marilyn’s clock culminated into an experience that questioned what might happen when varied perceptions of time collide. The piece ended with the action of Travis nailing his clothing to a wall, then ripping himself from the wall as if he were shedding his skin. He spit out extra nails that he held in his mouth, another indication he had endured a transformative process. After Travis nailed himself to the wall and tore himself free a second time, he stopped, releasing the entirety of the space back to Marilyn.

Jamie McMurry Flawed, 2013 photo by Philip Fryer

JAMIE MCMURRY FLAWED

The wall and floor of Jamie McMurry’s space was covered in faux-wood paneling. A white suit and various tools hung on the wall, while a dusty colored recliner awaited action in the middle of the space. The installation placed the audience somewhere reminiscent of a basement, a trailer, or a houseboat. A microphone on a stand was presented, making the space feel a bit like a makeshift nightclub. Wherever Jamie had taken us, it was steeped in nostalgia and felt a bit creepy. To add to this aesthetic, he used an over-head projector to share an article written on the 1953 murder of Mable Monahan. The article claimed that the only clues in the murder were 2 shoe prints and a bloody handprint smudged on the wall of the victim’s Burbank home (Jamie explicitly referenced this later in the piece by leaving his own imprints on the wall of his installation). He lunged in front of the article, one hand extended towards the projection, the other, jiggling a ring of keys attached to his belt loop. This action, like so many in the piece, oscillated between feeling antagonistic, ritualistic, and humorous.

He moved throughout the space, shifting between aggressive movements, ceremonial-like gestures, and childlike explorations of the body. He engaged in actions like gargling, gagging, and attempting to piss in a bucket. Many of his actions forced the audience to make quick decisions about proximity. He threw things around, created startling sounds, jumped rope with a long metal chain, and created slingshots that catapulted glass jars full of paint-covered wooden beads against the wall. Some may consider this irresponsible behavior, but I appreciated this tension as a strategy for breaking the traditional performance space.

Within the piece, Jamie engaged in a cycle of activating, referencing, and reframing images. We saw this first with an image of a palm tree. He wore the image on a T-shirt, projected it and proceeded to paint it on the wall in white. Jamie then spit the same white paint out of his mouth, referencing the tree through symbolic action. The most dynamic icon he used was an image of two hands in a gesture that is commonly read as “OK”. Between the hands was an oversized image of an open mouth. Jamie created this image with his own body in real time, referenced it on a t-shirt, and later recreated it on the wall. In one of the final actions of the piece, Jamie used a makeshift slingshot to throw one of his glass jars into a large vinyl print of the mouth. This action and the remnant of this action offered space to contemplate the notion of consuming experience.

Jamie McMurry Flawed, 2013, photo by Philip Fryer

Much of Flawed made use of actions that explored the complexities of consumption/excretion paired with the dichotomy of power/vulnerability. He addressed colonization, referencing the ghosts of the displaced. He wore an army blanket over his head, then after several moments, shifted the image by pushing his head through, turning the blanket into a poncho. When his head emerged, a pair of pantyhose he wore over his face had erased his identity. He ritualistically shook the glass jars he later fed to the mouth on the wall. He explored colonization again when he changed into a white suit that was embroidered with the words “GOOD PEOPLE ARE ALWAYS SURE THEY’RE RIGHT”. He then buried himself in a dirty recliner, covering his body in soil and mud. After raising himself from the dead, he attempted to destroy a wooden birdhouse with his bare hands. Watching Jamie expend so much effort, trying to destroy a home belonging to someone else, transformed him into the devil incarnate. Yet, the struggle of battling with his physical limitations illuminated his vulnerability, made him human, and somehow relatable. I couldn’t help but internalize this, becoming aware of my own arbitrary attachments. At what point does the struggle outweigh the perceived gain of a situation? Much of the piece existed in this area of grey.

Jamie McMurry, Flawed, 2013 photos by Philip Fryer

In addition to creating actions that demanded an upheaval of the audience, Flawed required multiple shifts in how the audience listened. Sometimes the audience was strained to decipher soft or muffled sounds. At other points in the piece, Jamie produced more abrasive sounds that resulted in the audience covering their ears. This varied sonic experience was a subtle call to action that foreshadowed the final action of the piece.

After playing Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe,” Jamie picked up a member of the audience, offered a private sonic experience by offering a pair of headphones, and carried them outside. When he walked through the Cyclorama’s doors, he was handed a bouquet of black balloons. As he walked down the sidewalk, the audience giggled and hustled to catch up. The lyrics “I’d trade my soul for a wish, Pennies and dimes for a kiss, I wasn’t looking for this, But now you’re in my way…Where you think you’re going, baby?…Hey, I just met you, And this is crazy, But here’s my number, So call me, maybe?” still fresh in our minds. A few blocks from the Cyclorama, Jamie stopped and released the balloons. Together, we all watched them drift through the night sky until they were out of sight.

VestAndPage Thou Twin of Slumber, 2013 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

VestAndPage Thou Twin of Slumber

The installation of VestAndPage (Verena Stenke and Andrea Pagnes) included a pile of broken glass with wine glasses hanging above, suspended in a moment of free fall. Two large bricks of ice melted throughout the day, requiring an occasional mopping around the space where they rested on the floor. The melting of the ice and the glasses frozen in time set the pacing of the performance before it even began. These materials were an indication that time would slow down in Thou Twin of Slumber. When the time came for the installation to be activated by the artists’ bodies, the piece began in darkness. A flame methodically illuminated a pair of legs hidden inside of a square shaped hole in the wall. I don’t remember the moment or how the lighting changed, but I remember seeing Verena’s body illuminated in the action of repeatedly falling onto a mattress as Andrea built a road of golden bricks that traveled across the space to eventually meet his collaborator. The inability to fully register the actions and where they fell into the timeline of the piece, seemed to be a consequence of the constant state of flux that erupted through the variances of low light situations. After learning that VestAndPage source content for their performances from their own dreams, I realized that this confusion was intentional, an effort to induce dream-like states in the audience. The collaborative duo spent much of the performance on opposite sides of the space, traveling towards one another. This resulted in the audience having to manage a tension between where to look. When giving attention to one artist’s actions, the viewer was forced to experience the other through their periphery. We had to use our other senses and call upon our intuition to gain an understanding of the totality of the performance. I had to make peace with the fact that I was going to miss much of the piece and that the action of forgetting and remembering, much like a dream, was built into the nature of the occurrence.

Andrea stood on a brick and carefully cut his face and chest in a mirror that was suspended in a similar fashion as the wine glasses. He followed this action by walking across the pile of glass. After seeing the blood from his body trickle from his carefully placed incisions, I prepared myself for the worst. The inner dialogue began and I anxiously tried to decide at what point I would intervene. At what point would it be negligent to watch another being put themselves in this kind of danger. As I looked closer, Andrea did not appear to be getting cut as he walked across the glass. This seemed impossible and I felt as though I had been tricked. Once I surrendered to the illusion, I was able to enjoy the beauty of the image and the sounds it produced. It was a seemingly impossible action made real, an action reserved for dream states.

VestAndPage Thou Twin of Slumber, 2013 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Meanwhile, Verena held a large glass jar containing a light, a piece of molding bread and larvae on her bare stomach. She sat close to the audience so that we could see the larvae’s movements. This was hypnotic. Andrea wore a contact microphone that amplified his breathing. Certain actions produced heavy and erratic breathing that broke my focus on Verena. I turned and saw his face in a container of sand, his breath captured in a dust cloud as he exhaled. When the two artists finally, physically met, Andrea was standing on one of the ice blocks. He gestured to Verena to stand on top of the ice with him. Placing the jar aside, she curled up into his arms and into what appeared to be raw wool that was wrapped around his form. The two tried to balance and hold one another as they slipped off of the ice.

In the action that followed, Andrea laid on the ice as Verena, randomly placed her foot into the hands of people in the audience. Similar to Travis’ use of ice, this action induced an empathetic response to the action that Andrea was enduring. Once her feet had reached a warmer temperature, Verena randomly chose people in the audience and led them one by one to Andrea. Andrea sat up, as Verena placed the audience member’s hand on his back. She continued this act of choosing and transferring until Andrea’s back was covered in hands. She illuminated this final image of the piece with a small and cool-colored light.

Our bodies are our vehicles for experiencing waking life, but like the decomposing bread consumed by the larvae, it does break down. It bleeds when cut. It is subject to extreme environmental conditions. It is vulnerable. Through the use of highly visceral actions, some that even appeared to defy physical reality such as walking on glass without harm, VestAndPage challenged ideas about what it means to be in a body and conjured romantic notions of what can be experienced beyond the physical realm.

When the lights lifted, Marilyn was still sitting, gently pushing her glasses across the table. I watched tears travel down her cheeks, as she maintained her uncompromising focus. Watching her travel through the subtleties of this process imparted her strength as an individual and the honesty behind her artistic practice. It reminded me of the first time I saw Bas Jan Ader’s I’m Too Sad to Tell You but without the buffer of a screen. I felt a deep gratitude for being witness to such candor unfolding in real time and space.

Jeff Huckleberry, Garden, 2013 photo by Phil Fryer

JEFF HUCKLEBERRY Garden

Near the end of the evening, Jeff Huckleberry engaged in a series of struggles. His installation was perhaps the most tactile, consisting of raw wood; some premade boxes that still had the bar codes stapled on them, balloons, buckets and power tools. Jeff paced around the space, before engaging in a series of cleansing actions. First, he poured a bucket of water and oblong balloons over his head. He followed this by drenching himself in rubbing alcohol, disguised in 2 Super Super Super Big Gulp travel mugs. In this quantity, the fumes were dizzying. Two clown noses dangled around his neck. He played the harmonica through a microphone and placed a hand held electric sander into a pile of ground coffee inside one of the premade boxes. It danced in circles as it droned, producing an intoxicating aroma of burning coffee and sawdust. He wrapped a long black cord, soaked with the rubbing alcohol, around his neck that looked like a contemporary ruff. He wrestled with a pile of wood in an effort to transfer it from a pile on the floor, into one of the wooden boxes. We watched him make one bad decision after another, simultaneously contemplating the consequences of each action. As he stood, hugging the pile of wood while being asphyxiated by the rope around his neck, I felt conflicted between the desire to unwrap him and the desire to laugh at the absurdity of what he was doing. I’d like to believe that my desire to intervene had been outweighed by my appreciation of the creative process, but in hindsight, I am not so sure. I ask myself if I chose to passively observe these actions because this was a “performance” or because I have the advantage of knowing Jeff’s work well enough to believe that he was “in control.” I also wonder if this choice was at all informed by Jeff’s physique. Maybe his strong-man-esque stature was fooling me into believing that he was somehow invincible. The fumes from the alcohol couldn’t hurt him. He couldn’t possibly slip and fall on the liquids pooling on the floor. This shifted my thinking to contemplate the shared human experience of struggling with the confines/potential of one’s own physicality and the inherent identities and perceptions of identities that it takes on.

Jeff Huckleberry, Garden, 2013 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Many of the actions Jeff engaged in either illuminated or exaggerated how cumbersome the body can be. His physical transformation through the rainbow, however, was something his body was well suited for. He stood, nude, inside a box, his legs placed in between the fallen wood that had previously served as his wrestling opponent. He dumped white paint over his on his head. He repeated this action: red, blue, orange, purple…He turns for a moment. The purple paint has trickled down his back in such a way that splits him in two. He is half orange, half purple. He continues with green paint, then blue. The watery paint moved over his form gracefully, pausing only as it gathered in his body hair. Jeff finished this action with yellow, and turned on a pump inside of the box. We watched as the brightly colored run-off paint turned into painter’s mud as it glided over the chaotic wooden structure. This action referenced the historic disciplines of both painting and sculpture while the clown noses spoke to history of ‘entertainment’. Although Jeff wore the signature of a clown, the ultimate entertainer, used colors that excite the eye, and cultivated an air of absurdity, the performance was far more than entertaining. Although Jeff did not utilize strategies that explicitly demanded active witnessing like Travis and Jamie had done, he succeeded in creating a community amongst the audience by engaging in actions that highlighted his own humanity. There was no room for the artist/performer to be placed on a pedestal in Garden. He was simply, one of us.

Jeff moved onto his next action that entailed filling a coffin shaped box with bottles of Miller High Life. He filled another coffin shaped box (slightly shorter) with the oblong balloons. He changed into a white shirt and pants that the residual paint on his body seeped through. This involuntary remnant left me to ponder our inability to fully control the imprints we make throughout our lives and the traces our bodies leave behind. He raised the boxes, mildly reminiscent of the twin towers, an image difficult not to conjure in our post 911 society. He broke the beer- filled box on the ground to release the beer onto the floor. He then engaged in a cycle of libation, pouring 1 beer on the box and 1 beer over his own head.

Jeff Huckleberry, Garden, 2013 photo by Phil Fryer

Nude once again, Jeff traveled the space hitting sticks, a ritual believed by the Ancient Filipinos to guide the departed to heaven. He left his installation to hit sticks in front of a photo of Bob Raymond displayed on a wall across the room. At this point, I had also left Jeff’s designated space, noticing that Marilyn was nearing the end of her action. I did my best to situate myself between them, an attempt to fully experience both pieces simultaneously. This action of mourning paid homage to Bob, while also establishing space for Edge within the structure of Garden by inviting the audience to cross over the assumed lines that separated the two pieces.

Jeff proceeded to turn off his sound, Marilyn’s clock echoing throughout the room. He transformed into a ghost while sitting inside of another box that faced the fountain he had previously made. Black liquid seeped through the white fabric that covered his form and poured down from a point on his head. He pulled the fabric off, revealing a tube inside of a bucket that continued to pump black water over his body. As the paint accumulated in the box beneath him he wore a black clown nose. This image evoked decay, leading me to contemplate embalming rituals and notions around preservation of the body. His clown nose suggested that this had all been a joke. The performance ended with 2 fountains made from matter, Jeff’s body no different than the pile of wood positioned in front of him. Like much of the work that unfolded earlier in the evening, Jeff’s actions created a dynamic tension around spectatorship and the importance of surrendering to process and allowing it to run its full course.

GJYD

Marilyn ends. One glass fell. The other glass followed several short minutes after the first. The crashing of the glasses on the floor was quick, less sonically jarring than expected, and seemingly anticlimactic. It was the moment when Marilyn left the table and disappeared into the shadows that my eyes started to burn, preparing to release tears. Several moments later, Phelan made an announcement and the experimental sounds of Bathaus began to play. My experience of processing what had just happened felt rushed. I wanted more time, more silence.

Marilyn Arsem, Edge, 2013 photo by Daniel S. DeLuca

Before the water that spilled from Marilyn’s glasses even had time to begin the process of evaporation, 3 figures wearing Gene Simmons masks swarmed Marilyn’s remnants. They played Ring-Around-the-Rosie around her table. When they stopped, they each revealed a roll of small black plastic bags that had been concealed in their hoodies. They pulled the bags one by one, littering the ground with plastic. I was offended by what appeared to be a lack of regard for the space created by the previous artist. It felt like I was watching someone dance on a grave. The action felt incomplete since they didn’t finish pulling through the entire rolls of bags. To inhabit a space where someone else had committed to a task with their full intention and presence just moments before, only to short- change their own action, was frustrating to witness. This oversight is a reminder of the importance of a site-sensitive practice and the power that can come from mindful considerations of the totality of a context and duration, as demonstrated by Marilyn’s piece.

GJYD, 2013 photo by Philip Fryer

In its best light, GJYD’s action pointed towards the varying understandings of death. Death does not discriminate and there are great variances between grieving processes. I faulted these performers for their insensitivity to Marilyn’s space, for their inability to acknowledge it as still being occupied, but perhaps they believed enough time had passed for the space to be activated by someone else. I, like so many, had been with Marilyn from the beginning of the day, thoroughly invested in Edge. GJYD’s action forced me to confront my own personal connections to Marilyn’s piece and the knowledge that NDPAE was dedicated to her late spouse. GJYD reminded me of the importance of practicing non- attachment even in the light of personal adversity.

____________

Performance artists have been organizing their own opportunities to share work for years. In the late 90’s and early part of the 2000’s, performance art was a medium that seemed to require gentle introduction to audiences across the U.S. It is not theatre, not dance, not music, and though it is related to visual art, what is called “art” is the creative process, rather than the product of a creative process. It is conceptual and often strange for new audiences. What is the etiquette for witness engagement? How do you know when a performance is over? Should one applaud? There are no answers to these questions, as each piece varies greatly depending on different artists’ intentions, philosophies and other circumstantial factors. Historically, the responsibility of inventing structures for presenting this work has fallen on artists and performance art organizers. Many of the early events and festivals that have occurred in Boston employed strategies that were used at NDPAE. Music was played between performances, other time-based media such as ephemeral installation and video were programmed alongside action-based pieces, and announcements were made to alert the audience when these action- based pieces had ended, an effort to alleviate any confusion. Within the context of NDPAE these strategies felt unnecessary, and at times, distracting. These details were initially frustrating, but have made me acknowledge how many changes the performance art scene in Boston has cycled through. There has always been a practice of patience among Boston audiences, but I believe that there has been an even deeper shift in how we collectively experience performance art in this city. Tools and strategies once used to calm the audience, to “loosen them up” are not needed in the way they once were. NDPAE illuminated the fact that audiences are more willing, equipped and wanting to engage in the dialogues that artists are putting forth without mediation. Audiences are prepared to invest in works that take on longer durations. This opens up potential to develop new experimental collaborations between creative minds connected through experiential practice. Instead of educating audiences on what performance art “is” and how it can be viewed, artists and organizers can instead focus our energies on developing multifaceted content that inspires deeper levels of creative and critical thought through the work we present.