The following is a collection of texts written by Sandrine Schaefer to archive Venice International Performance Art Week Polical Body-Ritual Body, 2014. Originally published on veniceperformanceart.tumblr.com.

The Liminal Body in Vela Phelan’s En Ti Confio and Alastair MacLennan & Sandra Johnston’s Let Liminal Loose

Text by Sandrine Schaefer

Liminality is frequently understood as being neither here nor there, an in between state that allows room for the ambiguous to take precedent. In the realm of anthropology, the liminal, also known as the marginal state, signifies the middle or transitional period endured in a ritual or rite of passage. The term has increasingly been used to attempt to describe the indescribable in performance art. Simultaneously, many performance artists strive to engage and explore liminality through their work. Within the context of the VENICE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART WEEK, where the ritual body was named as part of the exhibition’s theme, the liminal state was evoked in several live works, but most noticeably explored by two long durational pieces that unfolded throughout the week.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Vela Phelan, En Ti Confio. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

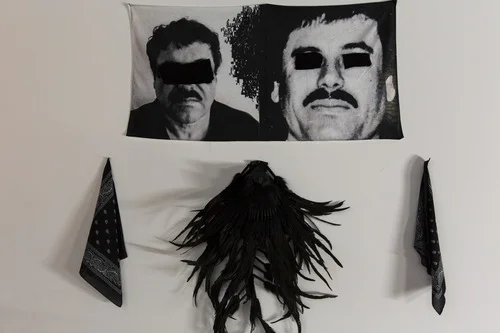

When encountering Boston-based artist Vela Phelan’s En Ti Confio, one enters a space that is illuminated by projector light emanating from a corner of the room. The images moving through the projection are pulsing with black and white shapes and pixels. The image of a statue on a television is one of the only recognizable forms coming through this intentionally skewed transmission. Objects, predominantly technological devices moving towards obsolescence, (tape recorders, record players, etc.) await action as they line the space where the wall meets the floor. In front of the projection, an altar has been constructed on the floor. On top of the altar is a small bust similar to that which is seen in the projection. Carefully composed on the walls are a variety of black objects: a feathered headdress, bandanas, black plastic bags, etc. Most notably, several towels are hung throughout the space that bear the image of the infamous drug trafficker, Juaquin El Chapo Guzman. Some towels have been imprinted with an image of Jesus Malverde, a Mexican Saint who in life stole from the rich to give to the poor. Both of their eyes have been blacked out with lines of black fur. This visual treatment of these portraits simultaneously references abduction posters, while pointing to the physical resemblance between these two men.

During the ART WEEK’s panel, Commemoration - Rites, Rituals and Daily Matters, Phelan points out the similarities in the faces of these two figures in Mexican culture and describes his fascination with them. Phelan explains that Jesus Malverde’s body was left to rot in the street when he died because of his thievery, yet 100 years later, he has been resurrected into Sainthood and celebrated for taking from the rich to give to the poor. Through this story, Phelan suggests, that El Chapo, named the most powerful drug trafficker in the world and undisputed murderer, could one day, like Jesus Malverde, become a “Saintly Sinner.” This notion of the Saintly Sinner evokes liminality, as Malverde is suspended in an in-between state, his character is neither good nor bad. El Chapo is treated similarly in En Ti Confio. In the space that Phelan describes as a “video altar action,” El Chapo is not painted as a villain, but sits alongside Malverde to be contemplated within the realm of the liminal.

Phelan’s actions within the space also flirted with liminality. The actions were often spontaneous and unconfined by the times designated by the exhibition’s program. Many of the actions occurred when Phelan felt compelled to do something, creating an air of chance around the piece. When Phelan did activate the space with his body, the actions always felt in service to the installation, in service to the “video altar.” Phelan stood with his fingers outstretched behind the altar on the ground. He walked around the space spraying rum from a cleaning bottle. He sat in a chair facing the altar and the projection in the corner. The modesty of these actions allowed the objects in the room to speak louder than the artist’s own body.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Alastair MacLennan and Sandra Johnston, Let Liminal Loose. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

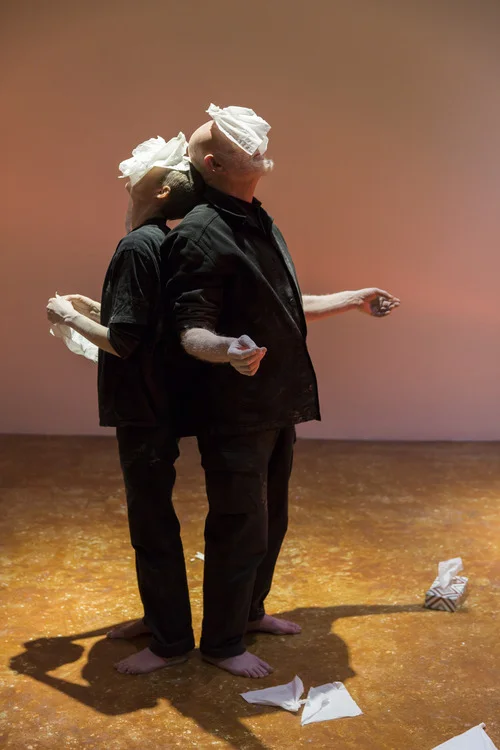

Nestled between 2 rooms on the first floor of Palazzo Mora, a rotting fish is nestled between the feet of Alastair MacLennan and Sandra Johnston, collaborating artists from Northern Ireland. The artists hold onto one another as they balance the fish’s dead weight between their feet and drag the fish across the floor. They are dressed similarly, wearing solid black that exposes their bare feet and bare heads. They are clearly individuals, but in this space, operating as a single being. This is pronounced by the shadow cast on the wall that makes it appear as if there is, in fact, only one body engaging in this action. In another action, MacLennan and Johnston stand back-to-back, palms face up, and heads pointed upwards. They each balance a single tissue on their face that gently captures minute vibrations produced by their breath. There are moments when this breath appears to be one breath, MacLennan and Johnston’s torsos expanding and contracting in unison. These slippages from two beings into one are common occurrences in this 5-day piece, titled Let Liminal Loose.

In the influential essay, “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites De Passage,” anthropologist, Victor Turner focuses on rites of passage practiced in several societies to examine the “sociocultural properties of the liminal state.”[1] In order to talk through these properties, Turner uses the term the “transitional being” to identify individuals enduring the liminal state. Turner states that during the liminal period, “the transitional being, passes through a realm that has few to none of the attributes of the past or coming state.”[2] This realm that Turner speaks of can be felt in Let Liminal Loose, and therefore, transforms MacLennan and Johnston into transitional beings, and at times, a single transitional being. Although it is clear that MacLennan and Johnston have taken great care in developing Let Liminal Loose, it is also apparent that the artists remain open to explore what arises in the present moment. By protecting this open space, the artists succeed in the intention put forth in their artist statement, “to keep each situation direct and without contrivance.”

Exploring this realm where qualities of the past and coming state are unknown, is not only reserved for MacLennan and Johnston. Witnesses to their work are also suspended in this state of unknowing. Upon entering the room on one day, Johnston precariously holds lit candles in her mouth beneath a heavy wooden table that is precariously balanced on one log. Meanwhile MacLennan drips hot wax onto the surface of the table. Various objects are scattered throughout the room (socks, trash, feathers, a box of tissues, branches, etc.) The space is filled with a constant state of action. On another day, Johnston and MacLennan are encountered, standing forehead-to-forehead. Their movements are modest and at times invisible to many viewers passing through the room. Nothing else is in the space except for a single flower petal between their feet. For the witness, there is no way of knowing what will occur from moment to moment, day to day. This unpredictability not only conjures the sensation that one is truly engulfed by the liminal, but also requires the audience to experience the work with heightened awareness.

The way that time operates in the work is also responsible for requiring heightened and active witnessing. In this room, time is in a perpetual state of slowing and shifting. In one of the early days of the piece, the artists move the table across the space. The pace begins in a way that is congruent with MacLennan’s methodical wandering. Then, Johnston pulls and pushes the table abruptly. This is followed by the artists adjusting to a shared pace. Because the artists have created and protected a space where time unfolds in a way that is both unexpected and unforeseen, this action does not feel aggressive, nor disruptive. The action creates a necessary shift that makes visible Johnston and MacLennan’s understanding of how time lives in one another’s bodies. It is nearly impossible for witnesses to these actions not to consider their own physical time-consciousness. MacLennan and Johnston’s treatment of time, both with one another and with the audience, maintains a space that invites one of the most fascinating qualities of Let Liminal Loose: the creation of the perpetual encounter.

One of the most compelling images of the performance begins when Johnston places a log on her chest and attempts to balance it between the weight of her own body and the wall. The log repeatedly falls. MacLennan notices this struggle, takes the log and places it to his own chest. Johnston stands, faces MacLennan and releases her weight into the log. As they stand balancing against one another, the log quite literally, becomes a conduit between MacLennan and Johnston’s bodies. What is so profound about this action is that it is an encounter that can only be realized through a series of encounters. The action requires MacLennan’s ability to step outside of his own action to acknowledge Johnston’s desire, and Johnston’s openness to accept his proposal to adjust the action. This image of transfer and translation recurs throughout Let Liminal Loose and results in creating a perpetual state of encountering that invites an opportunity to contemplate the complexity of human relationships with space, time, and one another.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | WenYau, Wish You Were Here. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

When an artist undertakes an action blindfolded, it undoubtedly makes them vulnerable to their audience. Although the removal of a sense allows the audience to experience a heightened empathic response towards an artist, the blindfold offers a far more complex experience. While blindfolded, an artist’s personal history with an action is exposed. If there is an immediate confidence while engaging in an action, we can assume that the action is one that they are familiar with. If there is hesitation, witnesses can assume that the action has been previously unexplored by the artist. When an artist is without sight, what is made visible, is the artist’s understanding of time, mediated through the chosen action.

Installed in a room on the 3rd floor of Palazzo Mora the phrase “I want real universal suffrage” has been repeatedly and methodically written in Chinese on half of the walls. In this piece titled, Wish You Were Here, Hong Kong artist WenYau is crouched on the floor, blindfolded with the national flag of the People’s Republic of China and wearing a t-shirt that reads “I Heart HK.” Wen Yau continues to repeatedly write the phrase in charcoal on the other half of the space without the sense of sight. Over the duration of approximately 4 hours, the writing not only fills the walls, but also spills onto the floor.

“I want real universal suffrage” is a phrase often used in protests of the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong in which Wen Yau is an active member. Upon Wen Yau’s arrival in Venice to create Wish You Were Here for the VENICE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART WEEK, police cleared the site that the movement had occupied in Hong Kong for the past 3 months. Being disconnected from her community during such an important time resulted in WenYau being moved to tears while performing this blindfolded action. As she wrote, WenYau allowed her witnesses insight into her relationship to the phrase and the power it holds for her.

The duality between the phrase written in an orderly manner next to the chaotic scrawling produced during WenYau’s blindfolded action furthers the complexity of the performance as it foreshadowed the piece’s ending. Several days later, Wish You Were Here was continued when WenYau returned to Hong Kong. In the final action of the performance, Wen Yau walks blindfolded, around the government buildings once occupied by protesters. As she traverses this location, she secretly writes “I want real universal suffrage” in places along her path. This action that was live streamed at the ART WEEK contextualizes Wish You Were Here in a way that otherwise could get lost in the magnitude of the exhibition. Through this action, the audience is reminded that although exhibitions like VENICE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART WEKK and performance art festivals prioritize the gathering of artists from around the world to share work, these artists must return to the places from which they come to continue their practice. Wen Yau endures the action of blindfolded writing in one space, yet never abandons the space that has inspired this action. The action cannot exist in Palazzo Mora or the former occupy site alone. These contexts must be linked through WenYau’s own body for the piece to be fully realized.

It is through this choice that Wish You Were Here serves as a refreshing example of the lineage that performance art shares with activism. The piece is made for an art-educated audience, protesters, and the public, and therefore, erases the boundaries between what is demarcated as “art action” and actions of the everyday. Furthermore, the blindfold illuminates the challenges of operating within the safety of an art-designated space vs. operating amongst an unknowing audience.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Alice Vogler, Liability of body. Language of liability. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

The blindfold also ignited dialogue around everyday actions in the final action of Boston-based artist Alice Vogler’s Liability of body. Language of liability. With ease and confidence, Vogler sits blindfolded on top of a plinth and fluctuates between repeatedly injecting her arms with needles and dropping small cards that depict life size images of the needles that she is using for injection. Even to the witnesses who do not know that Vogler is a Type 1 Diabetic, diagnosed in childhood, they can recognize that this action is so familiar to the artist that she can even do it with her eyes closed.

On the first day of the 2-day piece, Vogler sits at a table that holds a mountain of white sugar. She methodically fills empty pill capsules to make placebos for pre-made pill bottles that are also placed on the table. The bottles contain labels like “optimism,” “luck,” “fascination,” and “more time”. As she fills each bottle her demeanor changes and it becomes apparent that she is infusing each pill with an essence of the word written on the bottle. In this action, Vogler wears a mask and gloves. Not only does this create a physical barrier between Vogler and the audience, she also refrains from making eye contact or engaging with those who enter her space.

This changes dramatically in the second day of the performance upon the audience’s entrance into the space. Each audience member is greeted by an assistant and required to sign a waiver and release of liability. This form states that the undersigned knowingly assumes the responsibility of all risks and that they will not hold anyone affiliated with the VENICE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART WEEK responsible for any injury, disability or even death that could occur in the witnessing of the work. Those who refuse to sign the waiver are asked to leave.

Once the form has been signed, the audience must navigate thousands of clear marbles that are pooling on the floor. As Vogler stands in front of another plinth that holds a large glass bowl containing the marbles, she dips her face into the bowl, takes a mouthful, and spits them onto the ground. This repeated action is unpredictable. Sometimes she spits the marbles one by one, sometimes she simply opens her mouth and allows the weight of the marbles to send them tumbling to the floor. Sometimes the spitting is gentle. Other times, she spits aggressively and the marbles bounce across the floor, hitting the legs of audience members.

Like much of Vogler’s work, Liability of body. Language of liability is rooted in chance and choice and passively invites interaction. As Vogler spits marbles, another plinth presents the pill bottles that Vogler filled during the previous day alongside a bottle of water, a glass, and a cloth. As Vogler moves into her blindfolded action of injection, she lays out a paper explaining the side effects of sugar. The audience is never told to ingest the pills, simply offered a choice by positioning and suggestion. The majority of the audience ignore this subtle invitation until the moment that Vogler blindfolds herself. Once the artist’s eyes are covered people pool, like the marbles, around the pills and ingest. As this situation unfolds, witnesses also move close to Vogler’s body. Some photograph her, some observe her form, the needles and the cards at an intimate proximity. Regardless of the differences in how the interactions take shape, what is consistent, is that Vogler has created an experience that allows space for the audience to witness in ways that encourage collaborative viewing in which we all assume responsibility for our individual and collective safety.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Marilyn Arsem, Marking Time. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

Collective and nuanced witnessing is also called upon in Boston-based artist Marilyn Arsem’s Marking Time. Over 7 days, Marking Time spans 24 hours in which Arsem explores the seen and the unseen, the living and dead. Installed in a room are two black chairs, one that holds a bundle of black fabric that emits a faint aroma of rose to those who get close enough. The room contains a constant and soft ticking of a clock. This causes many to become mindful of their own pace upon entering the room. In the beginning hours of the piece, Arsem stands with her back to the chairs and stares out of a window, she also dressed in black. As she watches what is happening outside of the building, her breath is captured on the surface of the glass and illuminates smudges previously placed on the pane. This is a subtle acknowledgement of the space’s history. The curious thing about encountering a body in front of, or behind glass, is that the observer is required to navigate their own reflection. Arsem’s choice to engage with this aspect of the architecture sets the tone for the next 7 days. Marking Time is about reflection and invites the audience to explore their own relationships to time and ways in which it is marked in its passing.

As Arsem peers out the window, an insect flies by and catches her eye. Her curiosity ignites the curiosity of the others in the room. This is the first of many invitations for the audience to engage in a way that is unique within a traditional performance context. Some viewers stand and peer out other windows while others peak through a closet in the space that is slightly ajar. Many also occupy a close proximity to Arsem’s body. Her actions are modest and she often sits and stands in places in the room where the audience is gathered. In these moments, Arsem is not recognizable to all as “the performer.” This invisibility is shattered in the moments when Arsem looks around the room, engaging each person in eye contact. This tension between looking and being looked at continues to gain intensity throughout the weeklong duration of the piece. On the second day of Marking Time, Arsem introduces another black cloth and engages in various actions that include her covering and uncovering her body. In these variations of seeing and inviting herself to be seen, the cloth provides a similar function as the blindfold. Arsem’s actions with the cloth make her vulnerable, invite the audience to engage, and position time as the primary concept of the work, rather than something that is consequence or bi-product.

Throughout the week, Arsem creates an evolving relationship with the cloth, the chairs, and the black bundle that sits on one chair. In the final days of Marking Time, Arsem reveals that the bundle contains stones. This is not revealed, however, until Arsem has engaged in an action of holding the bundle in her arms for an hour. In this provocative image of an enduring body, Arsem’s body visibly breaks down. Her limbs tremble softly as it becomes apparent that this mysterious bundle contains substantial weight. This image adds an immense gravity to the actions that follow.

In the final hour of the piece, Arsem lies on the ground, covered by her cloth. The stones have been hidden once again, under the other cloth that has been removed from the chair and gathered on the ground in a way that resembles another covered human body. Because Arsem made several artistic choices that positioned the audience alongside her, many chose to endure the full 7 days of Marking Time. These witnesses wear their personal investment in the piece in their body language and facial expressions. Some lay on the cold ground with the two forms. Many cry silently. While Arsem offers her own covered body next to the visual suggestion of another, she is present, yet simultaneously she embodies the past and inevitable future of death that unifies us all.

In all three of these works, the blindfolded body is used as a strategy that breaks traditional witnessing and viewing behaviors that are often a consequence of “performance art’s” close semantic proximity to “performing arts.” In Wish You Were Here, Liability of body, Language of liability, and Marking Time, the audiences are not only considered, but positioned as active collaborators that are invited to engage in the creative processes necessary for these three works to be realized.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Benjamin Sebastian, 3 Cycles of Otherness. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

My body trembles with a rush of adrenaline as the walls and floor begin to vibrate with sound. Next to a drum set, Benjamin Sebastian stands wearing a black t-shirt, a cock ring, freshly tattooed blood lines that read “FROCIO” (faggot in Italian), and a thick rope that connects a pair of large antlers to Sebastian’s anus. As the drummer (Alessio Breda) wails on the drums, Sebastian screams the word “WOLF” repeatedly while facing a wall where the word is written upside-down. His voice is at full capacity, yet muffled by the drums. Beneath, a scanner and computer are positioned on the floor. Color images of Sebastian’s scanned body litter the space. As the drumming drowns Sebastian’s voice, it also infiltrates the other long durational works happening inside the chambers of Palazzo Mora. This action is in stark contrast to the quiet constant sound that has endured throughout the week’s long durational works and causes the audience to swarm and disseminate.

WOLF, a word significant in gay bear culture, is also FLOW, written backwards. This reads not only as a testimony for fluid identity, but also serves as an indication of the accumulating time-structure of the piece. 3 Cycles of Otherness uses unrelenting repetition to prioritize fragmentation as it unfolds over the duration of 3 hours for 3 days. This can be read through Sebastian’s use of sound that overwhelms and aggressively shifts the witnessing behaviors of the audience. As soon as the drumming starts, the witnesses in other parts of the building come to see what is happening. Many who are already gathered in Sebastian’s room leave because the sound is so loud. Some cover their own ears, furthering the action of muffling. Fragmentation becomes even clearer in the other 2 actions of the piece. Sebastion offers his skin to a tattoo artist (Marco Gazzato) who repeatedly tattoos his body with a word often used as a derogatory slur. Through the repetition, the word FROCIO, like the word WOLF, shifts through various meanings. Sebastian follows this action by pressing parts of his body onto the surface of the scanner. What is captured by the scan is then printed and scattered on the floor.

We witness the accumulation of these three actions through the medium of Sebastian’s body: the images of his form mediated by the scanner that are in a state of gathering on the ground, the loss of Sebastian’s voice, and the word FROCIO, presented on the surface of his skin, simultaneously in a state of fading and becoming. All of these actions prioritize a body that is fragmented by the time structure, as each action is precisely divided during each hour of the performance.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Bean, (m)other / the untitled (II). Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

In the same room, another 3-day piece was created earlier in the week by Sebastian’s collaborator, Bean. This piece, titled, (m)other / the untitled (II) served as a precursor to 3 Cycles of Otherness. Working with mantra and accumulating sound produced from the body that is then captured and mediated by recorded loops, Bean’s actions also invite sound to escape into the chambers of the space. On the 2nd day of (m)other, Bean’s body is positioned on the ground in a kneeling position, her head touching the ground. She repeats what sounds like the word “MASTER” over and over as she slowly moves into a standing and reaching gesture, pulling a black dress over her head. As her body expands, the word transforms from “MASTER” to “MASTOW” to “MYSTYLE,” etc. This process is recorded then played through speakers while she engages in other actions. This is played at a volume similar to the volume of Bean’s own chanting voice, complexifying the relationship between technology and human scale.

The disconnection of the voice from the body is the most powerful use of the fragmented body in (m)other / the untitled (II), although Bean uses other strategies to create accumulating fragments. Bean wears custom-made gold nipple shields in the shape of stag antlers that are attached to her nude body with a thin chain. From afar, the jewelrey creates the illusion that Bean’s body is cut where the chain hits her skin. This serves as a constant visual reminder of the fragmented body. Throughout all of the actions, Bean’s is illuminated by a large projection spanning 2 full walls of a breast being manipulated to produce milk. As the audience gathers along the walls, their collective form appears to be showered by the fluid.

(m)other / the untitled (II) oscillates between an acknowledgement of the surface body and the internal body, both through this larger than life projection and also in one of the most compelling actions of the piece. The center of the room is filled with old wooden laths. While crouching on the ground, Bean fills her mouth with a paste then sticks a piece of wood into her mouth while attempting to maintain eye contact with a member of the audience. Many look away from her after a few seconds, yet Bean remains in position until the paste has cured, at which point, she slowly releases the form from her mouth. The image could easily be equated with the voiceless/ silenced female body, yet Bean’s choice to engage with the audience in this way, turns this archetype on its head. The action acknowledges the time that it takes something to solidify and asks individuals in the audience to sit with the tensions that arise in this time.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Sarah-Jane Norman, Bone Library. Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

Sarah-Jane Norman’s Bone Library works with fragmentation of bodies that are human, animal, and ghost. Upon entering Bone Library, the audience is confronted with an oppressive odor emitting from ground bone. As one navigates through plastic walls, they see tables filled with bone fragments from hoofed animals that are overrunning Norman’s homeland. In a takeaway text included as part of the piece, one learns about what Norman describes as the catastrophic impact that sheep and cattle farming has on the Australian environment, endangering native animals and compromising the conditions necessary for the growth of native plants. On the tables one can see that each bone has been carefully inscribed with a word from an Indigenous Australian language that has been classified as extinct. In this exercise in archiving, Norman engages in an action of resuscitating a “dead” language while asking the audience to collectively take on this responsibility with her.

The smell of the room is so strong that it is difficult to spend time inside, yet Bone Library can be viewed from the third floor of Palazzo Mora. This point of view is ideal as it offers a view of the entirety of the space and the scale of the project and the impact it had on the audience over its 7-day duration. In the closing ceremony of Bone Library on the final day of VENICE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART WEEK, Norman offers the audience to take temporary custody of these bones. The room is packed with people eager to assist Norman in fully realizing this work. The ceremony begins with a “Welcome to Country,” a tradition where an elder gives a blessing before a cultural gathering in Australia. After Norman reads a letter written by an elder to offer this blessing, she invites the audience to choose a bone. Each bone is carefully wrapped and handed to each person with a certificate. By offering the bones into the care of people from across the globe, fragments of Aboriginal language are both scattered and preserved. This action echoes what is stated in Norman’s words of welcome during the closing ceremony, “a language can never really die when there is someone left to utter it.”

Language is at the forefront in Bone Library, but also an important subtext of ((m)other / the untitled (II), and 3 Cycles of Otherness. In all three of these works, the artists utilize fragmentation and strategies of repetition to position speech in a way that moves past its function as a necessity for communication. In these works, the potentiality of speech is explored and proposed as a political strategy.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Julie Vulcan | I Stand In (2014) Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

I have arrived at the moment that the body lying on the table is being released from Julie Vulcan’s touch. His skin is covered in oil, and as he opens his eyes, a look of surprise washes over his face. I suspect that he did not anticipate that there would be so many people gathered in the room to witness the encounter. Vulcan holds up a white cloth, an offering of privacy, the man wraps his body, and slowly disappears from the room. For 6 days, Australian artist Julie Vulcan will engage in one-to-one encounters that are witnessed by a larger audience in I Stand In, a performance that honors the forgotten, misplaced, unrecovered and removed. Vulcan asks participants to be surrogates for a faceless individual while she cleanses their bodies in a corpse-washing ritual. Before each body is released, the oil that has accumulated on their skin is pressed into a cloth. As the oil is absorbing, Vulcan writes a few words on the bottom right hand corner of the cloth in red ink. Each shroud is hung throughout the space, an evolving installation serving as a reminder of the bodies that have been offered in this testimony to the lost. As the shrouds accumulate and the cloth overlaps, the text begins to disappear, making the words scrawled across the bottom difficult to read. “Only you will have to live with this,” “A bloody hand and a piece of rock,” and “whispering light feeling” are a few of the phrases that I can decipher. The text conjures imagined last thoughts of the departed and/or evidence of those who have disappeared. As I watch the man leave the space and Vulcan begin to clean the table in preparation of her next exchange, I realize that I have walked into the moment that this ritual, as promised in Vulcan’s statement about the work, transforms from something to honor the dead, into something to honor the living.

Explorations of mortality and memory are prevalent among the long durational works during the 2nd VENICE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART WEEK 2014 Ritual Body – Political Body. The long durational performance program is treated similarly to the exhibition of performance art documentation that fills the spaces throughout Palazzo Mora in that each piece is given a room and the audience is invited to come and go as they please. This results in an unspoken tension. Each viewer must choose which piece to spend their time with, how long to stay, and are confronted with the impossibility of being able to experience the pieces in their entirety. This format can be criticized for unintentionally creating a sense of competition between the pieces and neglecting to offer a situation that invites the audience to stay for the evolution of the piece. However, what this format offers is an emphasis on the overlaps that organically occur between individual pieces as they unfold in the present moment.

Julie Vulcan’s I Stand In offers an experience that gently nurtures participants receiving the corpse washing who have been named as surrogates, yet creates further complexity in the choice to prioritize the action of witnessing these one-to-one encounters. This choice articulates the differentiation between the collective body; bodies that are unified in the present moment of sharing an experience, from the unified body; bodies unified in the erasure of difference and their experience of having been damaged in the name of development.

© photo by: Monika Sobczak | Melissa Garcia Aguirre | Desapareciendo / Disappearing (2014) Venice International Performance Art Week 2014

This use of the surrogate body is echoed in another work happening in the room that the audience must pass through in order to witness Vulcan’s piece. Mexican artist Melissa Garcia Aguirre’s Desapareciendo / Disappearing tackles tensions between the collective body and unified body through the use of delegated action. 5 stations are installed throughout the room. At each station, a performer dressed in white stands in front of a heavy wooden table that holds the tools that they will eventually activate. The cycle begins with one performer shucking corn kernels into a glass bowl. When the bowl is full, they pass the bowl to the second station where the kernels are counted and tallied on a sheet of lined paper. Once accounted for, the kernels are taken to the 3rd station where they are bathed in a bowl of water. At the 4th station, they are dried on a white cloth. When taken to the final station, the kernels are sent through a manual corn grinder where a pile of meal accumulates on the surface of the table. Each day, the performers move to the next station to experience each role in this assembly line.

The prioritization of the surrogate body is not only surfacing in Garcia Aguirre’s choice to design a human machine that is reliant on being enacted by 5 bodies simultaneously. The kernels, themselves also, become surrogates. Over the 7-day evolution of Desapareciendo / Disappearing, 30,000 kernels will go through this process, each kernel symbolizes the life of a person gone missing in Mexico since 2006.

Both Vulcan and Garcia Aguirre make visible bodies that otherwise would remain invisible. By seizing the help of others in achieving this goal, the audience is directly implicated into the work, whether they are explicitly participating in the action or witnessing it. Through the use of surrogacy, both I Stand In and Desapareciendo / Disappearing inspire a heightened empathetic response that emphasizes the potentiality of communal experience to understand loss on a global scale.